Hair loss in children can cause immense psychological and emotional stress to the patients as well as the parents. While most adults with a history of alopecia are able to reconcile themselves to a bald head, the situation in children is different. In children it can be very traumatic and is a common cause of low self-esteem and difficult socio-cultural adjustments. Alopecia in children may be one of the manifestations of a systemic disease or a disease entity itself. Several classification schemes for hair loss in children have been proposed, but none of these are perfect [1,2]. Most forms of alopecia demonstrate clinical and histological overlap. This blurs the distinction between diseases and makes classification difficult. The best approach would be to group diseases according to their aetiology, but this is impossible since the causes of many forms of hair loss are unknown.

The most widely accepted classification divides paediatric alopecia into congenital and acquired [3,4]. Hair loss in children can be subclassified according to: 1) abnormality in initiation of hair growth (genetic); 2) hair shaft abnormalities presenting with hair breakage; 3) abnormal cycling (anagen/telogen loss); 4) focal/diffuse alopecia (scarring/non scarring) [5].

The commonly encountered causes of alopecia in children include, tinea capitis, alopecia areata, traction alopecia, telogen effluvium, trichotillomania and all these are reversible if diagnosed early [6,7]. A thorough clinical history with careful examination (local and systemic), microbiological studies, trichogram and scalp biopsy will be helpful for the evaluation of paediatric alopecia. This holistic approach will be rewarded with correct diagnosis.

There are many clinical studies on paediatric alopecia, but limited studies on histopathological features [6-8]. The present study was carried out to describe histopathological features of alopecia in paediatric and adolescent age groups and categorize them into non scarring, scarring alopecias and miscellaneous causes.

Materials and Methods

The retrospective study was carried out for duration of 10 years (July 2006 to July 2016) in the Department of Pathology, PSG Institute of Medical Sciences and Research. Scalp biopsies from children aged 0 to 18 yrs with history of hair loss were included. Biopsies less than 2 mm in size and poorly fixed tissues were excluded from the study. The punch biopsies were kept in 10% formalin and processed in an automatic tissue processor (LEICA TP 1020) prior to paraffin embedding. Both vertical and transverse sections were taken and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. Special stains such as Verhoeff van Gieson (VVG) and Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff (AB/PAS) were used as required. The former was used to analyse the loss of elastic fibres in cases of scarring alopecia. The AB/PAS stain was utilised to assess thickening of the basement membrane and increase in dermal and perifollicular mucin.

Results

Over a period of 10 years, 130 scalp biopsies were received in the histopathology lab. A total of 35 children with hair loss (27%) from age group 0 months to 18 years were selected. Except for 2 biopsies that were 2 mm in diameter, the rest were 4 mm punch biopsies.

The distribution of these cases included 22 (63%) non-scarring alopecia, 6 (17%) scarring alopecia and 7 (20%) miscellaneous causes.

Details of non-scarring and scarring alopecia with histopathological features are summarized in [Table/Fig-1,2] respectively.

Clinical and histopathological features of non-scarring alopecias.

| Diagnosis | Sex | Age range | Clinical features | Histopathologic features |

|---|

| Female | Male |

|---|

| Alopecia areata | 10 | 2 | 10 month-18 year | Localized form-10Alopecia universalis-2 | Peribulbar lymphocytic infiltration, miniaturization, increased stelae, telogen follicles and nanogen follicles. |

| Trichotillomania | 8 | - | 8-18year | No clinical history suggestive of mood and anxiety (obsessive compulsive) disorders | Distorted follicular anatomy with collapse of the inner root sheath, pigment casts, trichomalacia, variably increased telogen follicles and intra follicular haemorrhage. |

| Traction alopecia | 1 | - | 15 year | Patchy hair loss with broken hairs and follicular prominence-since two yrs H/O traumatic hair styling | Increased number of telogen/ catagen hair follicles, stelae with no significant inflammation. An occasional hair follicle shows distorted anatomy and pigment cast. |

| Androgeneticalopecia | 1 | - | 18 months | Diffuse hair loss of three months duration | Miniaturization, altered T:V and A:T ratios, slightly increased fibrous stelae and telogen hair follicles |

Clinical and histopathological features of scarring alopecia.

| Diagnosis | No of cases | Sex | Age | Clinical features | HP Features |

|---|

| KFSD# | 2 | female | 8 and 13 years | Diffuse hair loss over the scalp, trunk and limbs with papular lesionSimilar complaints were seen in female sibling of one case.No ocular lesions in both cases. | Follicular plugging dilated infundibulum, perifollicular inflammation and fibrosis. Polytrichia was noted in one case |

| Tinea capitis | 1 | female | 14 years | Boggy swelling in the scalp with scaly patches of hair loss | Superficial and deep perifollicular, suppurative and granulomatous inflammation. Fungal spores (endothrix) within the hair follicle. |

| DLE† | 1 | female | 16 year | Hair loss with pruritic pigmented lesions in frontal region and face | Perivascular, perifollicular and perieccrine lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, BMZ‡ thickening, increased dermal mucin, full thickness scarring Direct immunofluorescence was positive |

| scleroderma | 1 | female | 18 years | Diagnosed case of connective tissue disorder with patchy hair loss over the scalp | Hair bulbs and follicles were surrounded by a thick sheath of hyalinized fibrous sheath, epidermal atrophy, homogenization of the upper dermis with loss of elastic fibres. |

| ESSA* | 1 | female | 15 years | Presented with bald patches of five yrs duration | Marked reduction in the number of hair follicles with eccentric epithelial atrophy and increased stelae. Atrophic sebaceous glands and many blank spots were present. |

*ESSA-End stage scarring alopecia. #KFSD- Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans

†DLE -Discoid lupus erythematosus. ‡BMZ – Basement membrane zone

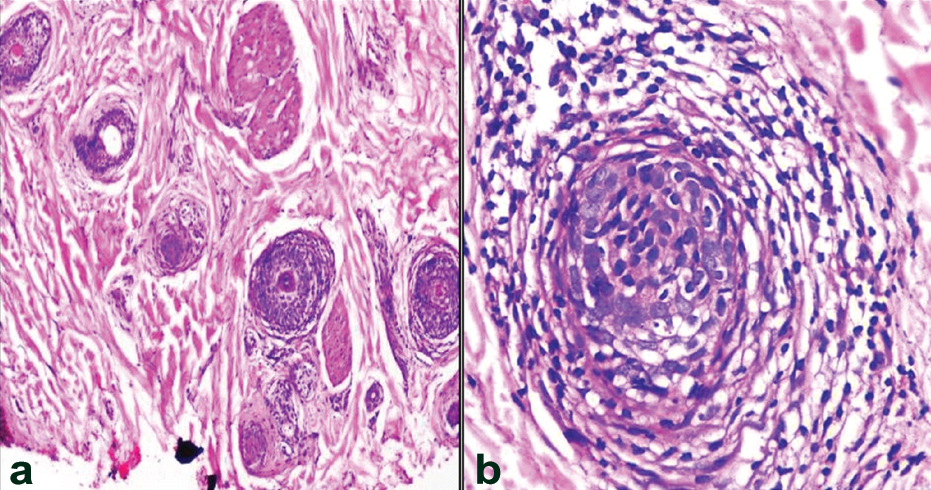

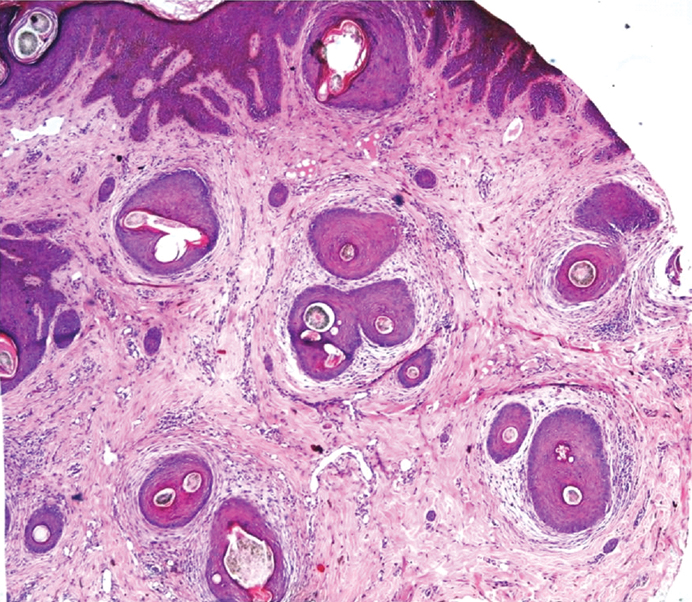

Among the non-scarring alopecia, there were 12 (54.5%) cases of alopecia areata [Table/Fig-3], 8 cases of trichotillomania [Table/Fig-4] and one each of traction alopecia and androgenetic alopecia.

Alopecia areata. Transverse section shows a) increase in telogen hair follicles with miniaturization (H&E, 10X). b) Peribulbar lymphocytic infiltration (H&E, 40X).

Trichotillomania. Transverse section shows hair follicles with Pigment casts, collapse of inner root sheath and telogenization (*). (H&E, 10X).

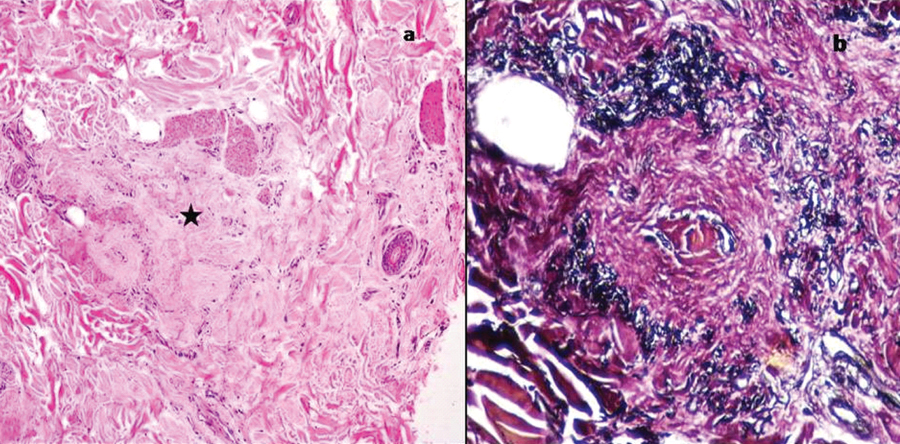

The group of scarring alopecia consisted of two cases of Keratosis Follicularis Spinulosa Decalvans (KFSD) [Table/Fig-5], and one case each of discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) [Table/Fig-6a], scleroderma [Table/Fig-6b], tinea capitis and End Stage Scarring Alopecia (ESSA) [Table/Fig-7].

Genetic causes such as vitamin D resistant rickets associated alopecia (two cases), and epidermolysis bullosa (one case) were included. Apart from the above causes there were three cases of short anagen syndrome and one case of nevus sebaceus.

KFSD. Transverse section shows polytrichia, perifollicular fibrosis and lymphocytic infiltration (H&E, 40X).

a) Perieccrine and perifollicular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in a case of DLE (H&E, 10X). Inset shows thickened basement membrane (AB-PAS,40X); b) Transverse section shows thick hyalinized sheath around the hair follicles in scleroderma (H&E, 10X).

End stage scarring alopecia; a) Scarred follicular unit: blank spot (*) (H&E, 10X); b) Loss of elastic fibres in areas of scar (VVG, 40X).

Clinical and histological features of miscellaneous causes are presented in [Table/Fig-8,9,10 and 11]. Epidermolysis bullosa: A neonate born to a 25-year-old G3P2L0 from third degree consanguineous marriage at 35 weeks of gestation presented with extensive bullous lesions and areas of skin peeling in most parts of the body. The child succumbed to death on day one and was submitted for autopsy examination. External examination showed extensive peeling of skin with diffuse hair loss over the occipital and temporal regions [Table/Fig-10a, b]. Internal examination revealed pyloric atresia, horse shoe kidney and urethral stenosis with dilated ureters and bladder [Table/Fig-10c]. Histopathological examination of scalp biopsy showed cleft at dermoepidermal junction and around hair follicles [Table/Fig-10d]. A diagnosis of Junctional Epidermolysis Bullosa (JEB) type was offered in view of severity of disease and involvement of internal organs. Previous two children had similar history and died on day one and three respectively. Genetic testing was suggested for parents to confirm the diagnosis and for selective embryo transfer in future pregnancy.

Clinical and histopathological features of miscellaneous causes of alopecia.

| Diagnosis | Number of cases | sex | Age range | Clinical features | Histopathological features |

|---|

| Vitamin D resistant rickets associated alopecia | 2 | female | 4 and 6 years | Clinically diagnosed Vitamin D resistant rickets presented with hair loss, which was patchy to start with, and progressed to become diffuse over a period of one year | Reduced number of hair follicles, irregular epithelial structures and infundibular type epithelial cyst |

| Epidermolysis bullosa | 1 | Male | Neonate | Extensive bullous lesions, skin peeling, diffuse hair loss, pyloric atresia, horse shoe kidney and urethral stenosis. Died on day one. | Cleft at dermo-epidermal junction and around the hair follicles |

| Short anagen syndrome | 3 | female | 3 to 6 years | Sparse hair growth with short fine brown hairs | Increased telogen hair follicles with reversal of anagen: telogen ratio, miniaturization of hair follicles with irregular and angulated outlines. |

| Nevus sebaceus | 1 | male | 4 years | Single hairless patch over vertex, noticed since six months of age. Slowly increasing in size | Hyperkeratosis with irregular acanthotic epidermis. Immature hair follicles with dilated infundibulum and abundant sebaceous glands |

Alopecia associated with Vitamin D dependant rickets; a) Irregular epithelial structures of hair follicles (H&E, 4X); b) Keratinizing epithelial type of infundibular cyst (H&E, 10X).

Epidermolysis bullosa: a,b) Generalized peeling off skin over face, chest, abdomen and back with diffuse loss of hair in occipital region; c) Specimen of stomach laid open showing pyloric atresia; d) sections from skin shows sub epidermal and perifollicular clefting. (H&E, 40X).

Short anagen syndrome: a) Scanner; and b) low power view showing increased telogen hair follicles (H&E, 40X and 10X).

Discussion

Alopecia is an unpleasant diagnosis at any age group. When it occurs in children, it is highly distressing to the parents, a challenge for the treating physician and has a negative psychosocial impact on the growing child. Elucidating accurate aetiology becomes a crucial step towards educating parents about available treatment options and prognosis.

Hair loss in paediatric age group could be congenital or acquired. Still it would be simpler to classify them into scarring and non scarring alopecia like in adults. There are a few conditions in children which cannot be categorized into either scarring or non scarring and these can be grouped under miscellaneous causes as done in the present study. Thorough clinical details, family history and histological findings are essential in making a right diagnosis. The common causes of paediatric alopecia are acquired and reversible. They include: alopecia areata, tinea capitis, trichotillomania, traction alopecia and androgenic alopecia.

In the present study, we have categorized causes of alopecia into non scarring, scarring and miscellaneous causes and will be discussed accordingly.

Non Scarring Alopecia

They accounted for majority of cases 22 (63%) cases. Among these causes, alopecia areata was the commonest followed by trichotillomania.

Alopecia areata (AA) was more frequently seen in female patients as in previous studies [7,8]. Female predominance can be explained because of its autoimmune basis, as autoimmune diseases are more prevalent in females. Laboratory evaluation of thyroid function, iron deficiency, blood sugar, HbA1c, serological markers of autoimmune diseases and testing for hyperandrogenemia are useful in the evaluation of patients presenting with alopecia. Though AA has bimodal age distribution (paediatric and adult) it is less likely to occur in children below 2 years of age [1,6,7]. In the present study, there were three patients (25%) below two years of age and the earliest onset of disease was in a 10 month old child. Diffuse AA, alopecia universalis and totalis are more frequent in children and in our study we diagnosed two children with alopecia totalis, accounting for 20% of cases of AA [6]. Histological features were similar to that of adult cases. Clinically, the localized form of AA can be confused with tinea capitis and trichotillomania and diffuse type with telogen effluvium and diffuse tinea capitis. This clinical challenge can be resolved by careful histopathological examination of the scalp biopsy [7].

Trichotillomania was the second most common cause of paediatric alopecia in our study and was noted to occur only in females. Trichotillomania is an impulse control disorder characterised by a long term urge that results in pulling out of one’s own hair. It is often associated with anxiety and may co-occur with other disorders of the obsessive compulsive spectrum [1]. It is more frequent in females as in our study. The classic histological features include collapse of the inner root sheath, pigment casts, intrafollicular haemorrhage and these were noted in most of our cases [10].

Although, predominantly a disease of adults, children are less commonly affected by androgenetic alopecia. However, some studies have reported androgenic alopecia as the second most common cause of hair loss in children and leading cause in adolescent age group [11,12]. Its occurrence in an eight month old girl child was an unusual feature of our study. The youngest case described in the literature is that of a six year old child [13].

Scarring Alopecia

Keratosis Follicularis Spinulosa Decalvans is a rare genodermatosis with X-linked and autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. It can also be sporadic in onset [14,15]. KFSD manifests as scarring alopecia mainly in male patients (females being carriers). In our study, two girls aged 8 and 13 years manifested with full blown disease, which has been reported in the literature [14,15].

Tinea capitis is common in children of tropical countries. It has varied clinical presentation such as hyperkeratosis of scalp, seborrhoea, alopecia and broken hair. Hair loss is non scarring type and reversible if treated early. When inflammation is severe, it can progress to scarring alopecia [16]. Though it is a common cause of hair loss, we had a single case of tinea capitis causing scarring alopecia. This is because most of the cases are clinically diagnosed with the help of Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) stained smears of hair shafts and are not biopsied. Other causes of scarring alopecia in the present study included connective tissue disorders such as Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE) and scleroderma. When biopsy is taken from scarred area or in late stages of the disease the diagnosis cannot be ascertained as was seen in one of our cases (end stage scarring alopecia).

Miscellaneous Causes

Vitamin D is essential for bone mineralization. Few studies have shown various cutaneous manifestations of vitamin D deficiency like psoriasis, atopic dermatitis, vitiligo, ichthyosis, keloid and autoimmune diseases and its role in treating the above [17]. Few experiments have demonstrated its role in hair growth signalling. The histological features are similar to that seen in atrichia with papular lesion and include absence of hair shafts, irregular epithelial structures and epithelial cysts [18]. Similar findings were observed in two of our cases. A good clinico-pathological correlation is essential to arrive at correct diagnosis.

Epidermolysis bullosa (EB) causing alopecia is a rare manifestation and it was diagnosed in one of our case. EB is an inherited bullous disorder that can manifest as milder form to fatal disease. It is classified based on the level of separation within the cutaneous basement membrane zone into EB simplex, junctional EB and dystrophic EB. Blistering involving basement membrane zone of hair follicle is the cause of hair loss. Other manifestations include mild hair shaft abnormalities, cicatricial alopecia and alopecia universalis [19].

We had three cases of Short Anagen Syndrome (SAS). There are very few case reports of SAS in literature and one case was reported from India [20,21]. SAS is a recently described entity characterized by persistent short hair due to shorter anagen phase. It has characteristic clinical presentation i.e. short smooth hair since birth and diagnosed based on reversal of anagen: telogen ratio on trichogram, the normal ratio being 9:1. Scalp biopsy also shows increased telogen hair follicles with a mild perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate and non-scarring type of alopecia [22]. A few reports from the literature revealed, SAS can have autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance and has a self-limiting course with spontaneous resolution at puberty [23,24].

There are some unique findings in present study: 1) unusual age at presentation (<1 year) in cases of alopecia areata and androgenetic alopecia 2) a full blown phenotypic expression of KFSD in females, who are generally carriers 3) rare causes of alopecias such as Vitamin D resistant rickets associated alopecia and short anagen syndrome were identified.

Limitation

The pitfall of the present study is the limited number of cases, though the study was carried out for 10 year duration. This is because not all cases of alopecia are biopsied routinely. Diagnosis is established based on its clinical presentation and ancillary techniques like KOH preparation, trichogram, and hair pull test. Biopsies are performed, when the diagnosis is not arrived on clinical grounds or the patient is not responding to treatment.

Conclusion

To conclude, alopecia areata is the commonest cause of hair loss in children. Good clinico-histopathological correlation is necessary to arrive at a correct diagnosis. Based on this, parents can be counselled about appropriate treatment options and prognosis.

*ESSA-End stage scarring alopecia. #KFSD- Keratosis follicularis spinulosa decalvans

†DLE -Discoid lupus erythematosus. ‡BMZ – Basement membrane zone