Smile indicates pleasure, amusement or derision on an individual’s face. Smile also expresses friendliness, appreciation, compassion and/or agreement. It can be used in treatment planning by the dentists. The branch of Orthodontics deals with facial aesthetics and function and establishes a harmonious occlusal relationship between the maxillary and mandibular teeth to achieve the same [1]. Orthodontists cater to most of their patients by improving their facial aesthetics or smile [2]. The facial aesthetics have great social value and so the orthodontists include it into their treatment planning [1,2].

Smile aesthetics of an adolescent is guided by his/her personal experiences, peer influences and social environment and can have a greater influence than the opinion of their orthodontists. Further factors like the educational and social status, cultural differences can have an impact on perception of smile [3]. Ethnic and racial differences play an important role in aesthetic dental smile which can differ among individuals of various populations and countries. Hence, orthodontists and general dentists should consider various factors to manage smile aesthetics in a more satisfying way [1].

The orthodontist’s aesthetic perception may not be in accord with the adoescent’s perception or the referring dentist’s perception [4]. Aesthetics plays an important role in justifying orthodontic treatment, both during childhood and adulthood especially from the patient’s point of view [5]. Classification of aesthetics requires a calibration of perception between orthodontist, dentist and patient. If this perception is not calibrated, conflicting opinions regarding the treatment expectations can surface [1]. Hence, the aim of the study was to evaluate and compare the preferences regarding smile arc, gingival display, midline symmetry, shape and size of incisor teeth, buccal corridor space and smile index of adolescent subjects between late adolescents, general dentists and orthodontists.

Materials and Methods

The present cross-sectional study was conducted between 1st September 2019 to 31st January 2020 among randomly selected general dentists, orthodontists and late adolescents of age ranging from 16-18 years, studying in premedical year at Ibn Sina National College for Medical Studies, Jeddah. Using rule of thumb, there were seven variables measured on five point rating scale among adolescents males, adolescent females, orthodontist and general dentist, at 80% power of the study, considering a minimum sample of 10 for each variable plus 50, thereby determining the sample size required as 400. Thus, the samples obtained for the study were 52 orthodontists, 111 general dentists and 275 adolescents (156 females, 119 males).

The study was performed after explaining the design to each participant, obtaining their written consent for participation and obtaining the Ethical Clearance Certificate from the institution. (Ref No: RC-19-23112017).

Each participant was shown the photo album that consisted of 7 sets of photographs each of one male and one female adolescent subjects of Arab ethnicity based on 7 variables: smile arc, gingival display, midline symmetry, shape and size of incisor teeth, buccal corridor space, ratio of central: lateral incisor and smile index. Each variable had digitally altered 5 male and 5 female subjects’ photos except the buccal corridor and smile index variables which had 3 digitally altered photos of each. The criteria for selection of the subjects whose smile photographs were used included: pleasing smile with Angle’s Class I occlusion along with full complement of dentition with no diastemas, crowding, rotations that might alter the perception of the evaluators. The male subject was 18 years and female subject was 16-year-old. The subjects who volunteered to give their smile photographs were selected on the clinical basis such that their measurements closely matched the standard values. The smile photographs were taken when participant was in a relaxed position and had a full, natural smile, with a natural head position using a digital camera (Nikon D200, Tokyo, Japan) positioned at 1.8 meters. The photographs were then edited using Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems) to produce five different desired measurements. Symmetrical image of each photograph was obtained using a ruler present on the computer screen to represent the actual size of the patient’s teeth. The modifications were done to obtain the desired smile aesthetic discrepancy. The alterations of the image were chosen after consultation with experienced orthodontists and data obtained from available literature [6,7]. The values clinically determined were measured again and also verified on the printed copy of the photographs. Minor imperfections of skin on the area of face were corrected by using Adobe Photoshop CS5 (Adobe Systems).

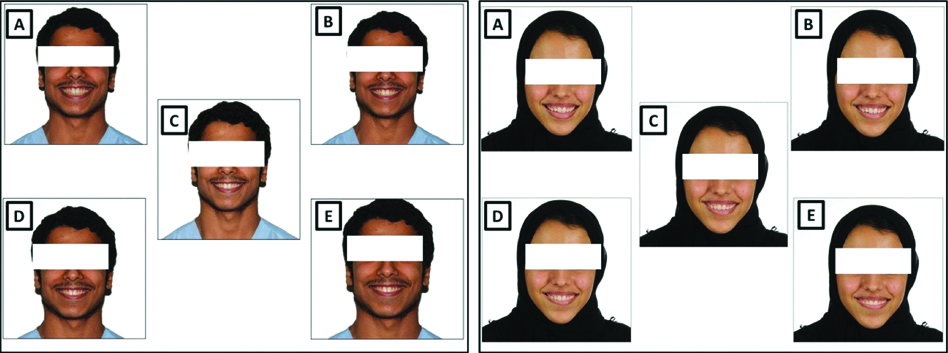

Set 1: Position of incisal edge of the maxillary central incisors [Table/Fig-1]

Position of incisal edge of the maxillary incisors: Curvature of the incisal edges of the maxillary incisors: (A) Shortened by 2 mm to the curvature of the lower lip; (B) shortened by 1 mm into the curvature of the lower lip; (C) at the same level; (D) extending 1 mm into the curvature of the lower lip; (E) extending 2 mm into the curvature of the lower lip.

Ideal smile arc is characterised by synchronic relationship of arc formed by maxillary teeth and lower lip on smile. The position of the incisal edge of the maxillary incisors was adjusted by shortening or extending 1 mm and 2 mm increments in tune to the curvature of the lower lip [Table/Fig-1A-E].

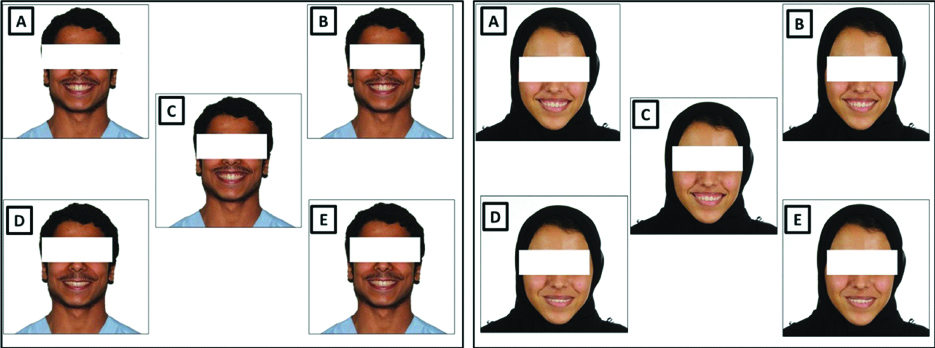

Set 2: Gingival display in the upper anterior region [Table/Fig-2]

Gingival display in the upper anterior region: Distance between upper lip and gingival margin of the maxillary incisors: (A) 2 mm (gingival); (B) 0 mm; (C) 4 mm (gingival); (D): Upper lip covers the gingival margin of the maxillary incisors by 4 mm; (E) Upper lip covers the gingival margin of the maxillary incisors by 2 mm.

In the ideal position, the distance between upper lip and gingival margin of the maxillary incisors will be 0 mm. The gingival display was altered by 2 mm, 4 mm increments either by decreasing or increasing their relative position to the upper lip [Table/Fig-2A-E].

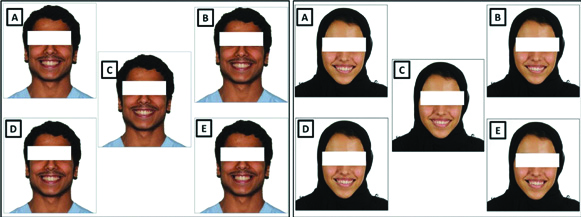

Set 3: Midline symmetry [Table/Fig-3] [8]

Midline symmetry: Dental midline shifted to (A) right by 3 mm; (B) right by 1 mm (C) right by 2 mm; (D) Normal dental midline (E) right by 4 mm.

The dental midline is a vertical line of contact observed between the two maxillary central incisors. It is perpendicular to incisal plane and parallel to the facial plane. Facial midline coincides with two anatomical landmarks Nasion and base of the philtrum. The dental midline was altered using increments of 1 mm to one side i.e., 1 mm, 2 mm, 3 mm and 4 mm to create variables [Table/Fig-3A-E].

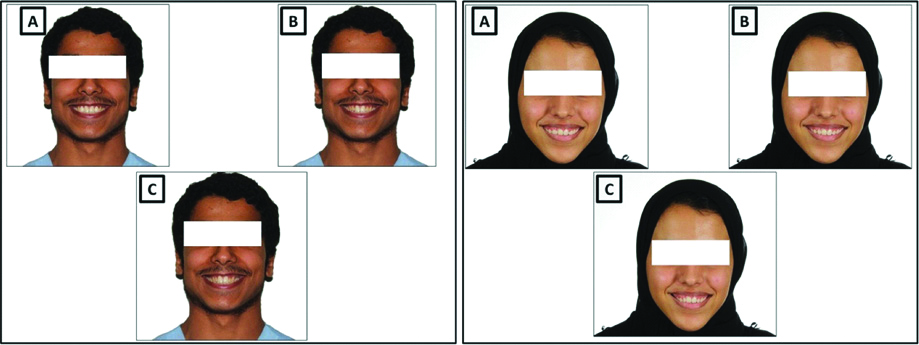

Set 4: Shape of teeth [Table/Fig-4] [9]

Shape of teeth: Alteration of four maxillary incisors: (A) Reduced cervico-incisal length by 25%; (B) Sharper mesio-incisal and disto-incisal angles; (C) Increase in cervico-incisal length by 25%; (D): Normal shape; (E) Rounded mesio-incisal and disto-incisal angles.

The normal shape of maxillary incisor teeth is considered to be (1); Sharper mesio-incisal and disto-incisal angles of all four maxillary incisors (2); Rounded mesio-incisal and disto-incisal angles of all four maxillary incisors (3);Vertical increase in cervico-incisal length of four incisors by 25% (4); Reduced cervico-incisal length of four incisors by 25% (5) [Table/Fig-4A-E].

Set 5: Buccal Corridor space [Table/Fig-5] [10]

Buccal Corridor space: incremental increase: (A) by 15 %; (B) by 5%; (C) 0%; (D) by 10 %; (E) by 20 %’.

Buccal corridors (negative or black spaces) are the spaces between the facial surfaces of posterior teeth and the corners of lips during smiling. The original photograph was adjusted so that no dark spaces may be observed between the molars and the inner commissures of the lips on both sides. These photographs produced an image with a broad smile (0% BCS). The BCS was then digitally modified to add 5% increments of dark space, from 0% to 20%. This produced five images with different amounts of BCS [Table/Fig-5A-E].

Set 6: Golden proportion [Table/Fig-6] [11]: Central Incisor: Lateral incisor teeth

Golden proportion: (A) Increased the width of lateral incisor; (LI) by 1 mm to central incisor; (CI); (B) Average crown width of maxillary CI and LI; (C) Increased width of LI by 2 mm to CI.

As per Golden proportions, the upper lateral incisors should be 0.618 of that of central incisors measured from their contact point. The maxillary lateral incisors’ crown width was altered and accordingly three images were obtained: Average crown width of maxillary lateral incisor (a); increased the width of lateral incisor by 1 mm (b); increased the width of lateral incisor by 2 mm (c) [Table/Fig-6A-C].

Set 7: Smile index [Table/Fig-7] [12]

Smile index: (A) Normal smile index; (B) Increased smile index by 25%; (C) Decreased smile index by 25%.

The smile index was obtained by dividing the inter-commissural width by the inter-labial gap (width/height) and accordingly the ratio was increased and decreased by 25% to obtain 3 photographs [Table/Fig-7A-C].

Each variable consisted of male and female photos and the images were labelled alphabetically. Hence there were 5 photos of incisal edge, 5 photos of gingival display, 5 photos of midline symmetry, 5 photos of shape of incisor teeth, 5 photos of buccal corridor space, 3 photos of Golden proportion and 3 photos of smile index. Each participant had to grade the photographs of male and female subjects separately. The time to evaluate each image was limited to 1 minute. In Best-Worst Scaling (BWS), participants are presented with a small subset of items (typically less than 5) and select the “best” and “worst” (most and least attractive, etc.,) items from that set [13]. BWS comparable to Likert ratings as a method of measuring facial impressions: it better predicts participants’ rankings of faces and shows greater test-retest reliability [14].

Statistical Analysis

The data obtained from all the participants were entered into the Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA) and subjected to comparison between the groups using Chi-square test. The statistical software used was IBM SPSS version 20. The level of significance chosen for the study was p≤0.05.

Results

Out of the total subjects who participated in the study, 156 of them were adolescent females, 119 were adolescent males, 111 were General dentists and 52 of them were Orthodontists. All of them performed the smile evaluation of the subjects completely. The mean ages of the orthodontists, general practitioners and adolescents were 38.19±8.23, 28.09±5.41 and 18.13±2.64 years, respectively. The orthodontists and general dentists had an average experience of 9.20±7.23 and 8.74±6.04 years, respectively.

[Table/Fig-8] shows that when observing the smile of female subject, all the four groups preferred that incisal edge of upper anterior teeth just contacts the lower lip without any gap or overlap. The least preferred option among all groups was when the lower lip overlapped the incisal edge by 4 mm. However, there was no statistically significant differences in the preferences regarding position of the incisal edge to the lower lip between the four groups (p=0.133). When observing the smile of male subject, all the four groups preferred incisal edge of upper anterior teeth just contacting the lower lip without any gap or overlap and their least preferred option was lower lip overlapping the incisal edge of upper incisors by 4 mm. There was a statistically significant difference in the preferences regarding position of the incisal edge to the lower lip between the four groups. Orthodontists did not prefer any overlap of upper incisors by lower lip in contrast to all the other three groups.

Preferences regarding incisal edge position between the groups.

| Incisal edge position of adolescent female subject |

|---|

| -4 mm | -2mm | 0 | +2 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 5 (3.2%) | 12 (7.7%) | 73 (46.8%) | 35 (22.4%) | 31 (19.9%) | 0.133 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 4 (3.4%) | 5 (4.2%) | 57 (47.9%) | 28 (23.5%) | 25 (21%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 3 (2.7%) | 2 (1.8%) | 46 (41.4%) | 22 (19.8%) | 38 (34.2%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 24 (46.2%) | 14 (26.9%) | 14 (26.9%) |

| Incisal edge position of adolescent male subject |

| -4 mm | -2 mm | 0 | +2 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 13 (8.3%) | 6 (3.8%) | 88 (56.4%) | 16 (10.3%) | 33 (1.2%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 6 (5%) | 7 (5.9%) | 73 (61.3%) | 8 (6.7%) | 25 (21%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 4 (3.6%) | 6 (5.4%) | 67 (60.4%) | 18 (16.2%) | 16 (14.4%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 26 (50%) | 14 (26.9%) | 12 (23.1%) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

The preferences regarding the gingival display during smiling is shown in [Table/Fig-9]. For the female subject, all the groups preferred either gingival display of 2 mm or no gingival display. The least preferred option was upper lip vertically overlapping the incisor by 4 mm. There was a statistically significant difference in the perception between the groups regarding gingival display (p=0.0001). Most of the Orthodontists and adolescent males preferred gingival display of 2 mm whereas most of the general dentists and adolescent females preferred no gingival display. All the orthodontists did not prefer when the gingival display was either more than 4 mm or less than 2 mm. For the male subject too, all the groups’ preferred gingival display of 0 mm followed by 2 mm. The least preferred option was upper lip vertically overlapping the incisor by 4 mm. There was a statistically significant difference in the perception between the groups regarding gingival display (p=0.001). In contrast to the Orthodontists, 31.5% of adolescent females, 22.7% of adolescent males and 27.9% of general dentist preferred gingival display of -2 to -4 mm.

Preferences regarding amount of gingival display between the groups.

| Gingival display of the adolescent female Subject |

|---|

| -4 mm | -2 mm | 0 | +2 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 5 (3.2%) | 14 (9.0%) | 67 (42.9%) | 61 (39.1%) | 9 (5.8%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 6 (5%) | 1 (0.8%) | 38 (31.9%) | 46 (38.7%) | 28 (23.5%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 1 (0.9%) | 11 (9.9%) | 50 (45%) | 39 (35.1%) | 10 (9%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 22 (42.3%) | 30 (57.7%) | 0 (0) |

| Gingival display of the adolescent male Subject |

| -4 mm | -2 mm | 0 | +2 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 11 (7.1%) | 38 (24.4%) | 54 (34.6%) | 46 (29.5%) | 7 (4.5%) | 0.001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 4 (3.4%) | 23 (19.3%) | 41 (34.5%) | 31 (26.5%) | 20 (16.8%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 5 (4.5%) | 26 (23.4%) | 41 (36.9%) | 26 (23.4%) | 13 (11.7%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 20 (38.5%) | 20 (38.5%) | 12 (23.1%) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

With regard to the midline symmetry [Table/Fig-10] of the female subject, orthodontists accepted only up to 2 mm of deviation of midline in contrast to other groups. 30.8% of adolescent males, 25.2% of adolescent females and 26.1% of general dentists accepted a midline deviation of 2 to 4 mm. This difference was statistically significant (p=0.0001). Similar perception was observed while observing the midline of the male subject (p=0.007). Orthodontists accepted only up to 2 mm of deviation of midline in contrast to other groups.

Preferences regarding the midline symmetry between the groups.

| Midline shift to the left of the female subject |

|---|

| 0 | +1 mm | +2 mm | +3 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 48 (30.8%) | 28 (17.9%) | 32 (20.5%) | 29 (18.6%) | 19 (12.2%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 38 (31.9%) | 35 (29.4%) | 16 (13.4%) | 22 (18.5%) | 8 (6.7%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 30 (27%) | 25 (22.5%) | 27 (24.3%) | 23 (20.7%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 8 (15.4%) | 16 (30.8%) | 28 (53.8%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Midline shift to the right of the male subject |

| 0 | +1 mm | +2 mm | +3 mm | +4 mm | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 75 (48.1%) | 35 (22.4%) | 22 (14.1%) | 12 (7.7%) | 12 (7.7%) | 0.007 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 47 (39.5%) | 34 (28.6%) | 22 (18.5%) | 9 (7.6%) | 7 (5.9%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 62 (55.9%) | 25 (22.5%) | 18 (16.2%) | 3 (2.7%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 22 (42.3%) | 12 (23.1%) | 18 (34.6%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Preferences regarding the shape of teeth for female subjects [Table/Fig-11] revealed significant differences (p=0.0001) and suggests that, most of the groups preferred them to have either normal shape of anterior teeth or increased cervico-incisal length except for adolescent males who preferred them to have sharp incisal angles on mesial and distal sides. However with regard to male subject, all the groups preferred when there was either an increase in mesio-distal width of anterior teeth or rounded incisal edges. Normal shape of anterior teeth was preferred significantly more by Orthodontists when compared to other groups. The intergroup perception comparison was significant (p=0.0001).

Preferences regarding shape of the teeth between the groups.

| Shape of teeth of the female subject |

|---|

| Normal | Incisal angles sharp on both sides | Incisal angles rounded on both sides | Increased cervico-incisal length of anterior teeth | Increased mesio-distal width of anterior teeth | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- females (n=156) | 73 (46.8%) | 22 (14.1%) | 7 (4.5%) | 46 (29.5%) | 8 (5.1%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- males (n=119) | 31 (26.1%) | 40 (33.6%) | 10 (8.4%) | 25 (21%) | 13 (10.9%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 45 (40.5%) | 13 (11.7%) | 6 (5.4%) | 40 (36%) | 7 (6.3%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 14 (26.9%) | 14 (26.9%) | 12 (23.1%) | 12 (23.1%) | 0 (0) |

| Shape of teeth of the male subject |

| Normal | Incisal Angles sharp on both sides | Incisal Angles rounded on both sides | Increased cervico-incisal length of anterior teeth | Increased mesio-distal width of anterior teeth | p-value |

| Adolescents- females (n=156) | 28 (17.9%) | 5 (3.2%) | 38 (24.4%) | 7 (4.5%) | 78 (50%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- males (n=119) | 22 (18.5%) | 8 (6.7%) | 26 (21.8%) | 18 (15.1%) | 45 (37.8%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 9 (8.1%) | 3 (2.7%) | 48 (43.2%) | 3 (2.7%) | 48 (43.2%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 14 (26.9%) | 0 (0) | 12 (23.1%) | 0 (0) | 26 (50%) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

[Table/Fig-12] reveals that in female subject, all the groups preferred that the space was not present. Orthodontists were the only group which did not appreciate when the BC was more than 5% and this difference was statistically significant (p-value=0.001). With regard to male subject, all the groups preferred that the space was not present. Most of the Orthodontists (80.82%) preferred when there was no BCS when compared to other groups (p=0.0001).

Preferences regarding Buccal Corridor space [BCS] between the groups.

| BCS of the female subject |

|---|

| 0% BCS | 5% BCS | 10% BCS | 15% BCS | 20% BCS | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 97 (62.2%) | 33 (21.2%) | 11 (7.1%) | 14 (9%) | (0.6%) | 0.001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 58 (48.7%) | 25 (21%) | 20 (16.8%) | 9 (7.6%) | 7 (5.9%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 61 (55%) | 23 (20.7%) | 14 (12.6%) | 8 (7.2%) | 5 (4.5%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 34 (65.4%) | 18 (34.6%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| BCS of the male subject |

| 0% BCS | 5% BCS | 10% BCS | 15% BCS | 20% BCS | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 51 (32.7%) | 49 (31.4%) | 20 (12.8%) | 29 (18.6%) | 7 (4.5%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 39 (32.8%) | 29 (24.4%) | 27 (22.7%) | 13 (10.9%) | 11 (9.2%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 34 (30.6%) | 39 (35.1%) | 20 (18%) | 12 (10.8%) | 6 (5.4%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 42 (80.82%) | 4 (7.7%) | 0 (0) | 6 (11.5%) | 0 (0) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Regarding the preferences with regard to ratio of central incisor and lateral incisor [Table/Fig-13], all the groups had a preferred normal ratio of 1:0.7 in the female subject. However, in contrast to other groups, only 46.2% of orthodontists preferred normal ratio (p=0.016). Regarding the male subject, most of the orthodontists and adolescent females preferred normal ratio of 1:0.7 whereas the general dentists and adolescent males preferred the ratio of 1:1. Between the groups, most of the Orthodontists (69.2%) preferred normal ratio and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.0001).

Preferences regarding ratio of central incisor: Lateral incisor teeth between the groups.

| Ratio of central incisor : Lateral incisor teeth of the female subject |

|---|

| Normal 1:0.7 | 1:1 | 0.7:1 | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 115 (73.7%) | 21 (13.5%) | 20 (12.8%) | 0.016 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 78 (65.5%) | 24 (20.2%) | 17 (14.3%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 77 (69.4%) | 13 (11.7%) | 21 (18.9%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 24 (46.2%) | 16 (30.8%) | 12 (23.1%) |

| Ratio of central incisor : Lateral incisor teeth of the male subject |

| Normal 1:0.7 | 1:1 | 0.7:1 | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 95 (60.9%) | 52 (33.3%) | 9 (5.8%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 44 (37%) | 60 (50.4%) | 15 (12.6%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 48 (43.2%) | 53 (47.7%) | 10 (9.0%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 36 (69.2%) | 12 (23.1%) | 4 (7.7%) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

[Table/Fig-14] reveals that all the four groups preferred the normal smile index among male and female subjects. Orthodontists did not appreciate when there was an increase in smile index by 25% in contrast to other groups (p=0.0001).

Preferences regarding smile index between the groups.

| Smile index in the female subject |

|---|

| Normal smile index | 25% increase in smile width | 25% decrease in smile width | p-value |

|---|

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 130 (83.3%) | 23 (14.7%) | 3 (1.9%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 84 (70.6%) | 15 (12.6%) | 20 (16.8%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 89 (80.2%) | 19 (17.1%) | 3 (2.7%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 40 (76.9%) | 12 (23.1%) | 0 (0) |

| Smile index in the male subject |

| Normal smile index | 25% increase in smile width | 25% decrease in smile width | p-value |

| Adolescents- Females (n=156) | 143 (91.7%) | 4 (2.6%) | 9 (5.7%) | 0.0001 |

| Adolescents- Males (n=119) | 92 (77.3%) | 9 (7.6%) | 18 (15.1%) |

| General dentists (n=111) | 100 (90.1%) | 9 (8.1%) | 2 (1.8%) |

| Orthodontists (n=52) | 48 (92.3%) | 4 (7.7%) | 0 (0) |

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Discussion

Smile aesthetics and variables affecting it have been studied in the previous years and yet, the influence of its variables is not established especially in adolescents. Furthermore, it is observed that patients and dental professionals view smile aesthetics differently as suggested by the results of the present study. The photographs of a young adolescent woman and man was chosen to be displayed as reference in the present study as their smiles were better accepted as attractive according to the principles of aesthetics [15].

It would not be appropriate to evaluate aesthetics based only on hard tissue relationships because sometimes soft tissues do not respond predictably to hard tissue changes. Hence both hard and soft tissue relationships must be considered while planning orthodontic and orthognathic treatment [16].

In an ideal smile, the edges of maxillary teeth should be parallel to and in line with the lower lip. The incisal edge position is important for speech and producing sounds that begin with “F” and “V” [17]. Gingival display and its perception vary between individuals of different age and gender [18]. Many a times, restorative dentists overlook this maxillary gingival display during aesthetic assessment [19].

Periodontists preferred adolescents with no gingival display while smiling when compared with the laypersons [20], which is similar with dentists’ preference in the present study. It is reported that laypersons accepted gingival display of upto 4 mm whereas Orthodontists preferred a display range of 0–2 mm [21]. Correa BD et al., and Ker AJ et al., showed acceptable gingival exposure of 2 mm for maxillary central incisor and 1.2 mm for maxillary lateral incisor [22,23].

The importance of midline shift on orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning is justified by the large number of cases with this malocclusion treated by orthodontists. The minimum and maximum detected threshold for midline shift is reported to be 1.83 mm and 2.92 mm respectively [24]. However, no differences have been observed with ideal smile perceptions and upto 3 mm of midline deviation, highlighting the variability in perceptions [25].

It has been reported than midline deviation upto 2.2 mm is acceptable by both orthodontists and laypeople [26]. Interestingly, Kokich VO et al., found that orthodontists are more critical than general dentists when evaluating midline deviations and gingiva-to-lip distances [27]. There are studies where laypersons’ acceptability threshold for midline deviations varied from under 2 mm and to around 3 mm in other studies [28]. The perception of maxillary midline deviation is influenced by structures adjacent to smile such as lips, nose and chin.

Anderson KM et al., stated that shape of incisors was instrumental in anterior dental aesthetic perception and for masculine smiles, square or round incisors were considered to be more attractive [29]. Whilst the patients preferred ovoid incisors, dentists and technicians had strong preference for tapered-ovoid incisors [2]. Restorative dentists’ preference for females was round incisors. Orthodontists preferred females with round and square-round incisors. Laypersons had no preference regarding female incisor shape. Square-round incisors was preferred by all groups for the male images [29].

Literature does not provide any conclusive results for the ideal size of buccal corridor space and hence depends on the clinician’s opinion. A broad smile with no BCS has been accepted well and considered attractive by both orthodontists and laypeople. The orthodontists are more sensitive/critical about to minor changes in BCS than a layperson [7]. However, some orthodontists believe that BCS have minor aesthetic value; whereas others consider them as unattractive [30].

The general opinion is that only large buccal corridor spaces should be corrected [31]. Recent studies confirm that these spaces do not influence rating of smile by either laypeople or dentists and have minimum impact on smile aesthetics [32]. But excessive BCS is considered unattractive both by the dentists and laypeople [33]. However, there is no reported difference in gender or age regarding aesthetics level of buccal corridors [34].

The smile index score is directly proportional to youthfulness of the smile [35]. However, this index lacks evidence based data to validate it. Age of a person significantly influences aesthetic perception. Individuals in younger age group are more critical about Smile Index and the position of Incisal Edge. Both smile index and incisal edge position have influence on how attractive the smile was in all age groups. Individuals with low smile index scores with higher or lower position of Incisal Edge were considered unattractive. When the smile index was medium or higher along with medium position of Incisal Edge, it was considered to be more attractive [36].

The tooth which shows largest variation in size is the maxillary lateral incisor. The size can vary from being small like a peg shaped lateral or failing to even present or develop altogether [37]. Orthodontists, dentists and the laypeople found the smile to be average when the width of lateral incisor was less by 0.5 mm [38]. The ratio of maxillary central to lateral incisor revealed the golden proportion in 50.3% of the students with an attractive smile and 38.1% in the non-attractive smile group.

In Saudi Arabia, males had wider anterior teeth with the central incisor tooth exhibiting a large gender-based difference. However, no size-dependent variation was reported for both genders [39].

It is reported that younger individuals rated differences more critically than older participants [37]. The primary subjects of the present study being of the adolescent age group responded critically which necessitates that such studies must be conducted to help the dentists and orthodontists to cater to their specific aesthetic needs.

Limitation(s)

Additional aspects such as variations in the lip framework, lip thickness, lip position in relation to the mandibular teeth or gingiva, affecting the smile aesthetics were not covered in the present study.

Conclusion(s)

The aesthetic perception of smile among Orthodontists and Dentists is believed to be having more similarities than differences when compared to adolescents. Understanding these differences would help the clinician to deliver more aesthetic treatment taking into account the preferences of adolescents as well as their treating dentists. Even the differences among the adolescents with regard to smile aesthetics can force the clinician to have an open mind and focus on these individual preferences thereby rendering individual based aesthetic treatment. However, further studies can be undertaken evaluating the factors such as variations in the lip framework, lip thickness, lip position in relation to the mandibular teeth or gingiva to further add to the knowledge of smile aesthetics can be undertaken.

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05

Chi-Square test; Level of Significance: p≤0.05