The Nasogastric Tube (NGT) insertion is a relatively easy procedure. That being said, it is not uncommon to see an anaesthesiologist trying a variety of methods to maneuver the tube into the oesophagus. Common problems during placement of NGT in anaesthetised patients are coiling of the NGT inside oropharynx [1], or around the endotracheal tube [2], kinking or bending, impaction around pyriform fossa or the arytenoids [3], and in rare cases, misplacement into the lungs [4]. Repeated attempts increase the risk of injury to the pharyngeal or laryngeal structures [5]. A clear understanding of the anatomy of larynx and pharynx can be used to manipulate a patient’s position during NGT insertion. Proper positioning and manipulation-based techniques may be advantageous over any instrument-based techniques in terms of smooth insertion and decreased risk of injury. Manipulation-based methods are reverse Sellick’s maneuver [6], and the Neck Flexion with Lateral Pressure (NFLP) technique [7]. Instrumentation-based methods are- Magill’s forceps assisted insertion, guide wire assisted technique [8], slit endotracheal tube technique [7], and the use of an intubation stylet [9].

At the time of designing this study, there was no clinical study reporting the success rate of this manoeuvre. A correspondence describing the manoeuvre [10], a case report detailing its use in a patient [11] and one review article [12] mentioning its principle of use was the only literature available regarding this technique. Thus, a lacuna was identified in the existing research. This study was therefore designed, to determine the proportion of patients in whom successful NGT placement was possible, applying either the SORT manoeuvre or the conventional blind method. Primary outcome measure was to determine the incidence of successful NGT placement using either SORT manoeuvre conventional or blind method and to compare between the two groups. The secondary outcome measures were to compare the procedure times and the incidence of adverse events between the two groups.

Materials and Methods

This interventional, single-blind, parallel group, randomised study was conducted in Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, a Government Medical College, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. The study spanned between February 2019 to April 2020, after receiving the approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (No. NMC/9997, dated 08.01.2019). Informed consent was taken from every patient prior to the study.

Inclusion criteria: All adult patients aged 18 years and above, undergoing elective abdominal surgeries that required intraoperative NGT insertion, were included for the study.

Exclusion criteria: Any anatomical/structural abnormalities such as cleft lip, cleft palate, deviated nasal septum and patients with nasal, oral, pharyngeal or oesophageal masses, those having significant injuries involving the head and neck region and those with thrombocytopenia or coagulopathies were excluded from study.

Sample size calculation: On review of previous literature [13] it was noted that the conventional blind method had a success rate of 50%. It was assumed that atleast a 20% increase in success rate using the SORT manoeuvre (as compared with the conventional method) was clinically significant. Thus, the effect size was taken as 0.20. Setting the confidence level at 95% (α=0.05) and the power (1-β) of the study at 80%, a sample size of 91 per group was obtained. Expecting a dropout rate of 10%, a final sample size of 101 for each group was considered Calculation of sample size, by comparing two proportions was done based on the following formula [14]:

where, a=Z-α value when alpha assumed to be 0.05. Here, a=1.96

b=Z-β value when power was assumed to be 80%. Here, b=0.84

x=the difference of success rate between the two groups. Here, 20%, hence, x=0.2

p1=success rate (proportion of patients having successful placement of NGT) using conventional blind technique. So, the value of p1=0.5

q1=1-p1=1-0.5=0.5

p2=success rate of proper NGT placement using SORT manoeuvre. It was assumed to be 70% with the assumption that there would be atleast 20% increase in the success rate using this new technique. So, the value of p2=0.7 and hence, the value of q2=1-p2=1-0.7=0.3 putting all these in the above equation, the sample size for each group comes to 90.16. It was approximated to 91. Considering a possibility of 10% dropout the final sample for each group was taken as follows: n-n/10 =91 or, 9n/10=91 or, n=101 (approx.). Hence, 202 was the total sample size for the two groups.

The ‘procedure time’ was measured from the time of insertion of the NGT into the nostril until the Nose-to-Ear-to-Xiphisternum (NEX) length had been inserted and checked. The placement was checked by auscultation for the ‘whoosh’ sound over the epigastrium. Correct placement of the tube within a single attempt was considered a successful insertion. Any adverse events occurring during the procedure were recorded.

Once the patient entered the Operating Room (OR), the Pre-Anaesthesia Checkup (PAC) was verified and the need for an NGT assessed. Intravenous access was established with an 18 G cannula for all the patients. Within the OR, the patient was continuously monitored for Electrocardiography (ECG), End Tidal Carbon Dioxide (EtCO2) and Oxygen Saturation (SpO2). The non invasive blood pressure was monitored continually. Premedication was given as appropriate for each patient, using inj. fentanyl (2 μg/kg), inj. glycopyrrolate (4 μg/kg). Induction was done with inj. propofol (2 mg/kg) or inj. thiopentone sodium (3-4 mg/kg) depending on patient variables. Intubation was done using inj. succinylcholine (2 mg/kg), a laryngoscope and an endotracheal tube of appropriate size. Muscle relaxation was maintained with inj. atracurium.

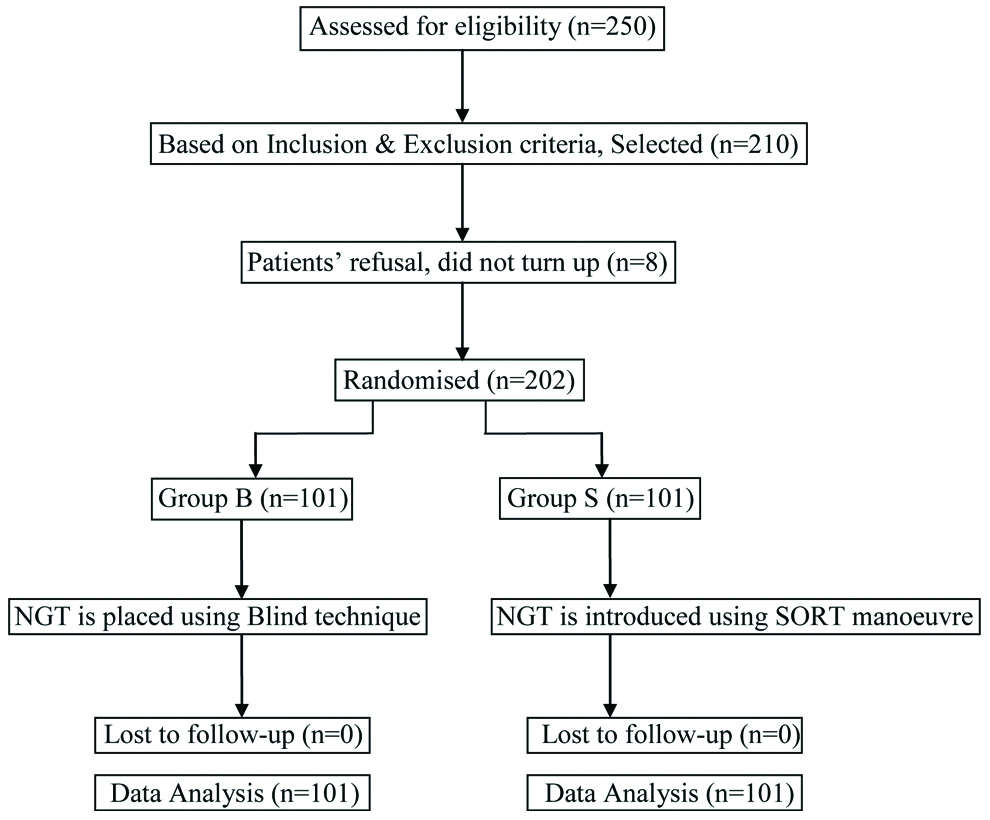

There were 202 sealed envelopes each containing a piece of paper marked as numbers ranging from 1 to 202. The envelopes were placed in a container and then reshuffled. After induction of anaesthesia, an envelope was randomly picked up and opened to find the number. If the number was odd the conventional blind method was followed (group B, n=101), and if the number was even the SORT method was followed (group S, n=101). The envelope was picked up from the container by one person who was not involved otherwise with the study. As the researcher had no control over the selection of method for NGT placement, and as the envelopes were randomly picked up (any envelope can be picked up revealing any number between 1 to 202), it can be said that selection bias was eliminated to some extent. The opened envelope and the paper were discarded each time. In both the groups, the endotracheal tubes were deflated prior to NGT insertion, and the tip of the NG tube was lubricated with 2% lignocaine jelly [Table/Fig-1].

CONSORT flowchart showing patient selection, randomisation and lost to follow-up.

In group B (conventional blind group), the NGT was inserted blindly, with the head in a neutral position, and no manipulation of the larynx. Instrumental assistance was also avoided in the conventional group [15]. Prior to insertion, the length of the NGT to be inserted was determined by measuring the distance from the ipsilateral nostril to the ipsilateral tragus, and further to the xiphoid process [8]. After insertion, the placement of the tube was verified by pushing 10 mL of air forcefully into the tube, and auscultating for a ‘whoosh’ sound. If the tube was found to be correctly placed in the first attempt, the case was counted as successful.

In group S (SORT manoeuvre group), the procedure as described by Najafi M et al., was used [11]. The head of the patient was first placed in the sniffing position, with the lower cervical spine flexed, and extension at the atlanto-occipital joint. This position was achieved with the help of a head ring placed underneath the occiput. The curvature of the NGT was oriented to align with the anatomy, while inserting from the nose to the oesophageal opening. The head was then rotated contralateral to the side of insertion. Finally, the NGT was gently pushed into the oesophagus using a twisting motion [11]. External pressure at the pyriform fossa was used in cases where coiling or kinking was suspected. Care was taken to avoid any extra force against any resistance. Any resistance was treated by withdrawing the tube a little and using ‘to and fro’ movements to re-insert the tube along the path of least resistance. As in group B, the epigastrium was auscultated to confirm the position of the NGT. Correct placement in a single attempt was considered a successful insertion.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were presented in number and percentage (%) and continuous variables were presented as mean±SD and median. Normality of data was tested by Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. If the normality was rejected then non parametric test was used. Quantitative variables were compared using Independent t-test/Mann-Whitney test (when the data sets were not normally distributed) between the two groups. Qualitative variables were compared using Chi-square test/Fisher’s-exact test. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data was entered in MS excel spreadsheet and analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0.

Results

Total 202 patients undergoing abdominal surgeries under general anaesthesia, and requiring intraoperative NGT placement were included in the study.

There was no significant difference between group B and group S with respect to age, weight, Mallampati, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status and gender distribution. Thus, the two groups are comparable in terms of demographic parameters [Table/Fig-2].

Demographic parameters of the study subjects (N=202).

| Parameters | Group B (n=101) | Group S (n=101) | p-value |

|---|

| Age (years) | 42.7±14.6 | 41.4±14.5 | 0.518 (Mann-Whitney test) |

| Weight (kg) | 56.1±11.3 | 55.94±12.5 | 0.819 (Mann-Whitney test) |

| Sex (F/M)† | 67/34 | 65/36 | 0.767 (Chi-square test) |

| ASA PS (I,II,III,IV)† | 45/53/2/1 | 43/49/9/0 | 0.11 (Fisher-exact test) |

| Mallampati grade (1/2/3)† | 44/40/17 | 42/44/15 | 0.834 (Chi-square test) |

All data have been expressed as mean±SD except those marked with ‘†’ which indicate as number of patients. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant.

ASA: PS American society of anesthesiologists physical status

NGT insertion was successful in 78 out of 101 anaesthetised, intubated, adult patients present in group B, whereas in group S 95 out of 101 patients underwent a successful NGT insertion, (success rate 94%, approximate). The difference between the two groups was significant, with a p-value of 0.0006 [Table/Fig-3].

Success rate of NGT placement.

| Success/failure | Group B (n=101) | Group S (n=101) | Total | p-value |

|---|

| Success | 78 (77.2%) | 95 (94%) | 173 (85.6%) | Chi-square value 11.636; p-value=0.0006 |

| Failure | 23 (22.8%) | 6 (6%) | 29 (14.4%) |

| Total | 101 (100%) | 101 (100%) | 202 (100%) |

Data expressed as number of patients. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

The procedure time was not normally distributed between the two groups. A non parametric test was therefore used to analyse the data. The median time taken in group S was 25 seconds, which was significantly higher than the median time taken in group B (22 seconds) [Table/Fig-4].

| Time taken (seconds) | Group B (n=101) | Group S (n=101) | p-value |

|---|

| Mean±SD | 26.9±17.0 | 26.0±7.5 | p-value 0.024(Mann-WhitneyU test value 41.67) |

| Median (IQR) | 22(17-28) | 25(21-30) |

| Range | 12-140 | 15-60 |

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

The overall incidence of adverse events was considerably higher in group B as compared to group S. Further introspective look in the data shows that coiling was the most common complication. The incidence of coiling was higher in group B as compared to group S. Other adverse events were also more frequent with blind technique. However, the rate of impaction was comparable between the two groups [Table/Fig-5].

Incidence of adverse events.

| Adverse events | Group B (n=101) | Group S (n=101) | Total | p-value |

|---|

| Coiling | 44 (43.6%) | 22 (21.8%) | 66 (32.7%) | 0.001(Chi-square test) |

| Kinking/bending | 27 (26.7%) | 9 (8.9%) | 36 (17.8%) | 0.0009(Chi-square test) |

| Mucosal injury | 26 (25.7%) | 4 (4%) | 30 (14.9%) | <0.0001(Fisher-exact test) |

| Impaction | 3 (3%) | 0 | 3 (1.5%) | 0.246(Fisher-exact test) |

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

The ECG, EtCO2 and SpO2 were monitored continuously for detection of any adverse event. The data was found within normal limit and was not analysed and not presented [Table/Fig-6].

| Parameters | Time of measurement | Group B (n=101) | Group S (n=101) | p-value |

|---|

| SBP (mmHg) | Before Insertion | 139.8±18.2 | 144.1±21.2 | 0.125* |

| After Insertion | 129.3±16.0 | 130.3±17.2 | 0.668 |

| DBP (mmHg) | Before insertion | 88.7±11.6 | 89.4±12.1 | 0.643 |

| After insertion | 82.5±11.0 | 82.2±9.3 | 0.482 |

| MAP (mmHg) | Before insertion | 105.7±12.8 | 107.6±14.1 | 0.264 |

| After insertion | 98.1±11.8 | 98.2±11.1 | 0.866 |

| Heart rate (Beats/min) | Before insertion | 96.5±12.6 | 99.7±14.2 | 0.063 |

| After insertion | 89.1±12.7 | 91.2±14.2 | 0.258 |

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance. All were analysed using Mann-Whitney test except marked * which was analysed using t-test.

SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; MAP: Mean arterial blood pressure

Discussion

The present study found that the success rate was considerably higher with SORT manoeuvre (94%) compared with conventional blind method (77.2%). This increased success rate of the SORT manoeuvre, a combination of four manipulations, is mostly attributed by modifying the position of the patient. Some of the methods that work by modifying patient’s position include the reverse Sellick’s manoeuvre, neck flexion [6], and Neck Flexion with Lateral Pressure (NFLP) [7] technique. Modification of the position of patient is a relatively safer method compared with techniques which rely on stiffening the NGT [7,12,16].

The first component of SORT, the Sniffing position, offers helps by keeping the NGT in close proximity with the posterior wall of pharynx, thereby facilitating smooth insertion of NGT into the oesophagus. This is somewhat similar to what we achieve with neck flexion technique [14]. The second component, Orientation, serves to align the natural curvature of NGT with that of the nasal passage and pharynx, thus avoiding unnecessary bending and coiling of the NGT. The third manipulation, the Rotation of head to the contralateral side, helps by compressing the pyriform sinuses and pushing the arytenoids medially. It works similar to lateral neck pressure technique [3]. The final step ‘Twisting’ movements which push the NGT gently into the oesophagus. The twisting movements are beneficial when any tube is to be inserted into a narrow lumen. For instance, while inserting a central venous catheter, the dilator that is inserted over the guidewire, is also pushed in using twisting movements. This provides for smooth progress of the dilator into the subcutaneous tissue tunnel. This twisting manipulation has therefore been utilised as a component in this manoeuvre.

The SORT manoeuvre prescribes rotation of the head to the ‘contralateral’ side (relative to the nostril used for insertion). The contralateral rotation is claimed to compress the ipsilateral pyriform sinus [10,11]. However, Bong CL et al., reported an 80% success rate in NGT insertion, using ipsilateral head rotation, instead of contralateral head rotation [17]. Further research would be required to understand the differences in anatomy caused by ipsilateral and contralateral head rotation, and how they influence NGT insertion. At the time of designing the present study, no previous research was available, regarding the success rate of the SORT manoeuvre. However, at the time of reporting the present study, a recent study became available where Sanaie S et al., reported the success rate of SORT manoeuvre to be around 90% in the first attempt compared with 17% using the NFLP technique [18]. The present study also has determined the success rate of SORT manoeuvre to be around 94%.

In the present study, the procedure time for the SORT manoeuvre was found to be significantly higher than the time taken for the conventional blind method. Although the mean values of procedure time were apparently comparable (26 second in both groups), an indepth analysis of data revealed a wide variation in the procedure time, i.e., the data was not normally distributed. Thus, the median values were given more importance than the mean values. In the present study, a considerably higher number of adverse events occurred in the conventional blind method of insertion, as compared with the SORT manoeuvre (approximately 54% vs 23%, respectively). In a recent study [18], the incidence of adverse events using the SORT manoeuvre was noted to be 31% which was comparable with the comparator group i.e., the NFLP technique.

The SORT manoeuvre appears to reduce the incidence of adverse events at the cost of prolonging the procedure time which is definitely a demerit of this novel technique. The longer procedure time and lower incidence of adverse events with the SORT manoeuvre in comparison with the blind technique can be explained by the following factors. The SORT manoeuvre being a four step manoeuvre, requires time for positioning the patient. While the patient can be placed in the sniffing position prior to starting the procedure, care has to be taken while rotating the head to the lateral side. The endotracheal tube must be carefully held so as to keep its position fixed before rotating the head. Thus, it is essential to do this step slowly, resulting in a lengthening of procedure time. In case of any hindrance or resistance during insertion, the NGT should be withdrawn slightly, and re-inserted, using to and fro and rotational movements to provide the NGT a scope to find a new path of least resistance. This repetitive movement could become a time-consuming affair, and contribute to the increased procedure time. In the blind method, the NGT is inserted in a straight forward movement, such that any resistance in the pathway is overcome by increasing pressure, rather than altering the course. The SORT manoeuvre seeks to avoid any resistance altogether. In other words, application of undue force is avoided altogether in the SORT manoeuvre. Thus, the essence of this manoeuvre is to reduce the incidence of injury, even at the cost of increased procedure time. Najafi M, the proponent of this novel technique, has emphasised this categorically in their original communication that the NGT should be inserted gently [11]. The manoeuvre is also claimed to be an easy to learn technique [19] which uses the first rule in medicine i.e., Do not harm at first. It is also a smooth process using anatomical approach without any instrumentation [20].

In the current study, a few issues were faced while performing the SORT manoeuvre, mainly during lateral rotation of the head. The endotracheal tube is generally fixed at the right angle of the mouth. In such a case, if the NGT were to be inserted in the right nostril, the head of the patient along with the fixed endotracheal tube, attached to the ventilator circuit, would have to be rotated to the left. In such cases, the contralateral rotation was found to be cumbersome. Extra care was required to ensure that the endotracheal tube maintained its position, as there was significant risk of dragging of the endotracheal tube to the left. Since, the cuff of the endotracheal tube was deflated prior to insertion there was also a risk of extubation during rotation of the head. Lateral rotation could also cause the endotracheal tube as well as the ventilator circuit to obstruct the view of the Anaesthesiologist. This complicated process could be avoided by keeping the endotracheal tube detached from the ventilator circuit during NGT insertion. However, keeping the endotracheal tube detached from the circuit during NGT insertion is not feasible in all patients, as procedure time can extend upto approximately 60 seconds, which may result in hypoxia in frail patients.

In the current study, auscultation of a whoosh sound over the epigastrium on pushing 10 mL of air rapidly through the inserted NGT was used to confirm the correct position of the NGT. This method does not require any aspirate and is therefore easily done at the bedside. However, the auscultation method also has several drawbacks. Transmitted sounds from an NGT that is present in the lungs, oesophagus, duodenum, or proximal jejunum may lead to a false positive confirmation of the NGT placement [21,22]. Thus, radiological confirmation of the NGT tip location is always mandatory prior to giving gastric feeds [21]. In the current study, NGT insertion was done, mainly for deflation of the stomach during laparoscopic procedures. The NGT was removed after the surgical procedure was completed. Therefore, auscultation was considered sufficient for confirmation in the current study.

Limitation(s)

Owing to unavailability of polyurethane tubes, the NGT made up of polyvinyl chloride was used. The use of flexible and soft polyurethane tubes, instead of polyvinyl chloride tubes could possibly have led to further reduction in the incidence of mucosal injuries, although the increased flexibility could have also led to more frequent coiling and kinking of the NGT. The verification of proper placement of the NGT was done by auscultation to detect the ‘whoosh’ sound. Other methods, such as pH paper testing, bedside ultrasound, or bedside x-ray would be more reliable methods for confirmation of correct placement of the NGT.

Conclusion(s)

To conclude, a higher success rate was achieved using the SORT manoeuvre for NGT insertion, as compared with the conventional blind method. The incidences of adverse events were also less when the SORT manoeuvre was used for insertion, as compared with the conventional blind method. Although procedure time was longer with SORT manoeuvre, the overall benefit to the patient was greater, as injury was avoided. Hence, the SORT manoeuvre is a feasible method for NGT insertion, particularly in cases where it is crucial to avoid injury, such as in patients with coagulopathies.

All data have been expressed as mean±SD except those marked with ‘†’ which indicate as number of patients. A p-value ≤0.05 was considered significant.

ASA: PS American society of anesthesiologists physical status

Data expressed as number of patients. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance

Data expressed as mean±SD. A p-value ≤0.05 denotes statistical significance. All were analysed using Mann-Whitney test except marked * which was analysed using t-test.

SBP: Systolic blood pressure; DBP: Diastolic blood pressure; MAP: Mean arterial blood pressure