The Indian relationship to alcohol may be defined as an “ambivalent drinking culture,” as while alcohol intake is largely discouraged, individuals who drink frequently consume excessive amounts. This dynamic greatly adds to the incidence of alcohol use disorder, which is a serious public health concern in India. The implications of this illness extend beyond the individual to include the entire family [1]. Numerous studies have found that alcohol consumption is responsible for most mental difficulties, including mood and anxiety disorders [1,2].

Individuals with alcohol dependency or abuse frequently have decreased social or occupational functioning due to alcohol use, legal concerns and disagreements with family or friends over excessive drinking. Alcohol use and life stress can cause psychological, biological and behavioural reactions that impair a person’s capacity to cope with emotional pain, raising the likelihood of developing psychiatric issues [5,6].

Anxiety disorders can be debilitating and often persist despite treatment efforts, leading to significant difficulties. A fascinating element of these illnesses is the interaction between genetics and life events. Although certain genes can predispose individuals to anxiety disorders, it is clear that traumatic events and stress also play a crucial role in their development [7]. Depression is characterised by feelings of melancholy, loss of interest and pleasure in activities. People suffering from depression frequently describe it as a tremendous emotional agony and they may struggle to convey their feelings through tears. A considerable proportion of people suffering from depression have suicidal thoughts and a significant number have attempted suicide. Common complaints among people with depression include low energy levels, trouble finishing chores, challenges at school or work and a lack of drive for new endeavours are common complaints among people with depression. Family members face several obstacles when living with someone addicted to alcohol. Alcoholism not only affects individuals consuming alcohol but also impacts those around them, making life difficult in various ways [8,9].

A study reported a significant association between alcohol use and dependence on mental distress among spouses, as well as an increase in mental disorders in a Norwegian population [8]. Another study conducted on the Indian population revealed comparable findings, indicating elevated rates of anxiety and depression among spouses of men with alcohol use disorders compared to those whose husbands did not use alcohol [10]. There is limited data available on the incidence and prevalence of mental disorders and psychological complications in spouses of patients with alcohol dependence. Thus, the present study aimed to assess the perceived stress levels and the prevalence of depression and anxiety and to explore the relationships between perceived stress, depression, anxiety and socio-demographic factors among spouses of individuals diagnosed with alcohol use disorder.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted between November 2021 and December 2021 at the Psychiatric Outpatient Department (OPD) of ACS Medical College and Hospital in Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India a tertiary hospital in the Chennai suburban area. The Ethical Committee at ACS Medical College and Hospital approved the study for further proceedings (No. 385/2021/IEC/ACSMCH, dated 20.10.2021).

Sample size: Based on a similar study done by Kishor M et al., (2013), which had a sample size of 60, 100 participants were recruited for the present study [2].

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria: The included in the study were spouses of patients who consecutively visited the Psychiatric Outpatient Department (OPD) and were diagnosed with Alcohol Use Disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 (DSM-5) criteria. Only spouses who consented to the study were included. Spouses of patients with psychiatric disorders other than Alcohol Use disorders or substance dependence were excluded from the study.

Study Procedure

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, was used to diagnose patients with Alcohol Use Disorder [11]. A sociodemographic proforma was used to collect details about the participants’ age, education, physical illnesses, employment status and the number and ages of their children. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) was used to assess the severity of depression, the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) to evaluate anxiety symptoms and the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) to measure perceived stress levels [12-14].

The HAM-D contains 17 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 4 for each item. A score of 0 to 7 is considered normal, while a score of 8 or higher indicates mild to severe depression [12].

The Hamilton Anxiety Scale consists of 14 items, with scores ranging from 0 to 4. Scores between 8 and 14 indicate mild anxiety, scores from 15 to 23 indicate moderate anxiety and scores of 24 or higher indicate severe anxiety [13].

The PSS includes 10 items. Scores from 0 to 13 indicate low stress, scores from 14 to 26 indicate moderate stress and scores from 27 to 40 are considered high perceived stress [14].

Data was collected from consenting participants who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria in a single sitting.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SPSS version 20.0 software. Demographic data were analysed using descriptive statistics, presenting means with Standard Deviations (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The continuous outcome variable was subjected to univariate analysis. The mean differences between the two groups were compared using an independent t-test, whereas ANOVA was employed to compare the mean differences across more than two groups. A p-score of <0.05 was taken as significant. Bonferroni multiple comparisons were conducted to further analyse the mean differences between more than two groups.

Results

The study revealed that the educational status of participants varied, with the majority having completed their schooling (81%), followed by 12% who were uneducated and 7% who had graduated. Regarding the employment status of the spouses, a significant proportion were employed (84%), while 16% were unemployed. The family structure among participants showed that nuclear families were the most prevalent (76%), followed by extended families (21%) and joint families (3%). On average, the participants reported having one female child (70%) and two male children (71%). A notable proportion of the participants were unemployed (46%), while 26% were partially employed and 28% were fully employed. Furthermore, the study noted that 19% of participants had a documented history of physical illness, whereas the majority (81%) did not report any known physical illness. Lastly, in terms of socio-economic status, nearly half of the participants were classified as lower class (49%), followed closely by those in the lower-middle class (48%), with a minority in the upper-middle class (3%) [Table/Fig-1].

| Variables | n | % |

|---|

| Educational status | Not educated | 12 | 12 |

| Schooling | 81 | 81 |

| Graduated | 7 | 7 |

| Employment status of spouses | Employed | 84 | 84 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 16 |

| Type of family | Nuclear | 76 | 76 |

| Extended | 21 | 21 |

| Joint | 3 | 3 |

| Presence of male child/children | Yes | 71 | 71 |

| Presence of a female child | Yes | 70 | 70 |

| The employment status of the patient | Employed | 28 | 28 |

| Unemployed | 46 | 46 |

| Partially employed | 26 | 26 |

| H/o known physical illness | Yes | 19 | 19 |

| No | 81 | 81 |

| Socio-economic status (Modified Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic scale) | Lower | 49 | 49 |

| Lower middle | 48 | 48 |

| Upper middle | 3 | 3 |

The average age of the participants was 42.1±11.7 years. The mean age of female children was 19.4±12.1 years, while male children had a mean age of 19±11.4 years. Regarding psychological measures, the average stress score among participants was 24.2±3.7, indicating a moderate level of perceived stress. The mean anxiety score was 19.2±6.4 and the mean depression score was 16.4±5.7 [Table/Fig-2].

Characteristics of the study participants.

| Variables | Mean±SD |

|---|

| Age (years) | 42.1±11.7 |

| Child female age (years) | 19.4±11.7 |

| Child male age (years) | 19±11.4 |

| Stress score | 24.2±3.7 |

| Anxiety score | 19.2±6.4 |

| Depression score | 16.4±5.7 |

Out of the respondents, six spouses did not report any depression; 29 reported mild depression, 30 had moderate depression, 17 suffered from severe depression and 18 had very severe depression. In terms of anxiety, five spouses did not report any anxiety; 13 respondents had mild anxiety, 61 had moderate anxiety and 21 had severe anxiety. Regarding stress levels, one respondent reported mild stress, 74 reported moderate stress and 25 reported high stress.

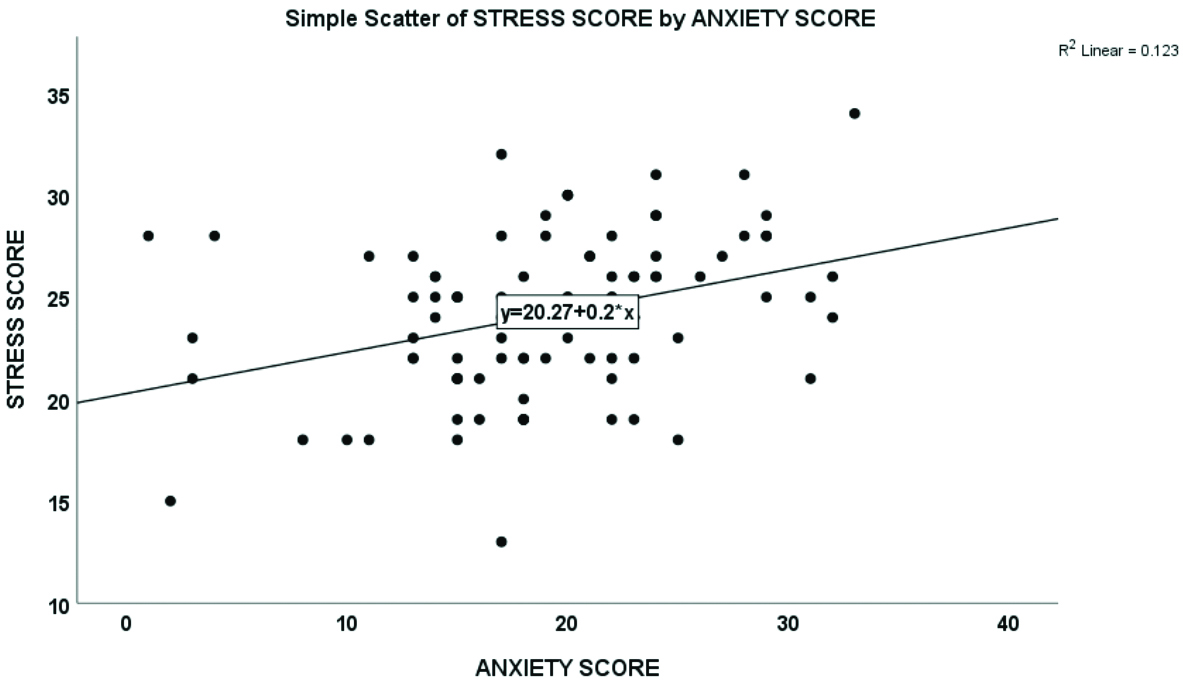

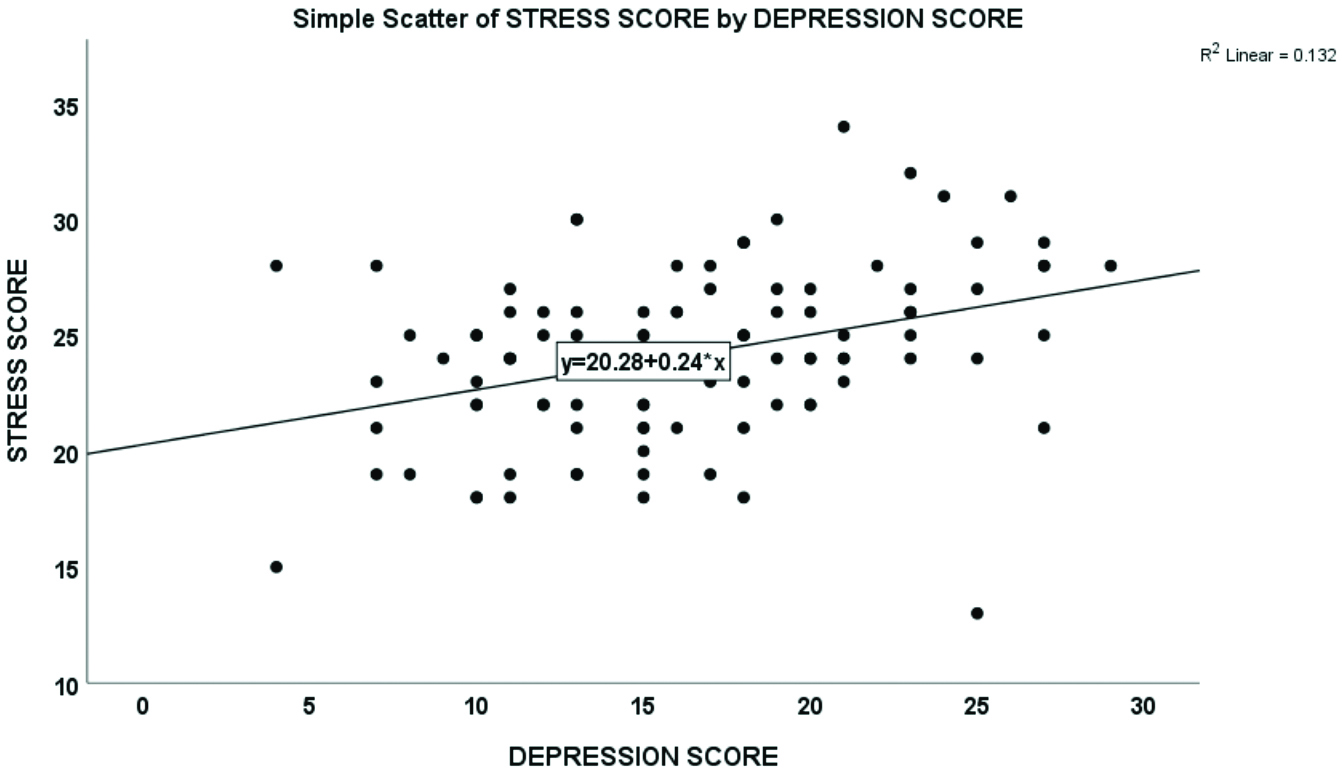

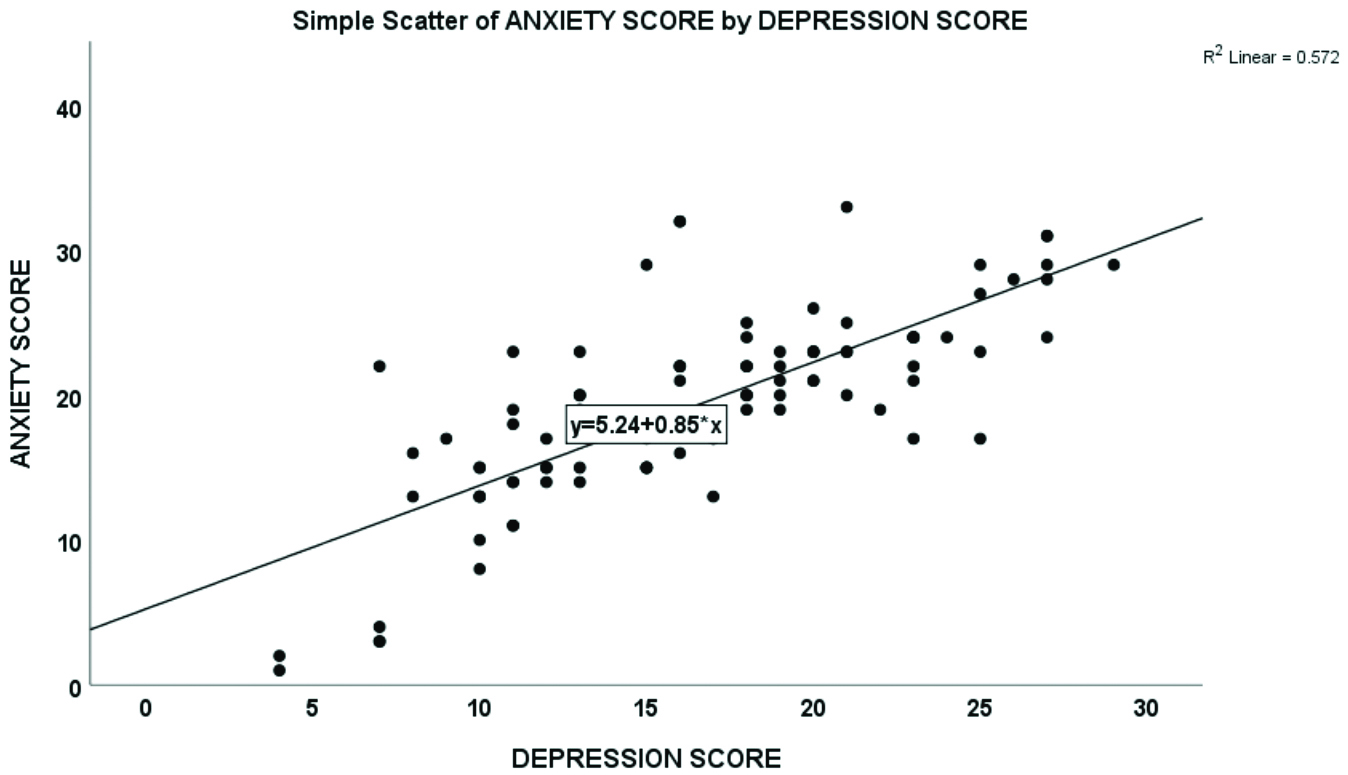

A significant positive correlation was reported between anxiety and depression scores. The Pearson correlation coefficient (rho) indicated a moderate positive correlation between stress and anxiety scores (rho=0.350, p<0.001) and between stress and depression scores (rho=0.363, p<0.001). Moreover, a strong positive correlation was observed between anxiety and depression scores (rho=0.756, p<0.001) [Table/Fig-3,4,5 and 6].

Correlation between stress, depression and anxiety scores of study participants.

| Correlation coefficient rho | Stress score | Anxiety score | Depression score |

|---|

| Stress score | Pearson’s correlation (rho) | 1 | | |

| p-value | | | |

| Anxiety score | Pearson correlation (rho) | 0.350** | 1 | |

| p-value | <0.001 | | |

| Depression score | Pearson correlation (rho) | 0.363** | 0.756** | 1 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

Correlation of stress score with anxiety score.

Correlation of stress score with depression score.

Correlation of anxiety score with depression score.

Significant associations were observed between the spouses’ employment status and psychological well-being. Employed spouses demonstrated notably lower stress (p=0.047), anxiety (p<0.001) and depression (p<0.001) scores compared to unemployed or partially employed patients [Table/Fig-7]. A significant association was observed between the presence of female child/children and anxiety scores, with those having female child/children had significantly higher anxiety than those without female children (p=0.012).

Association between sociodemographic variables with stress, depression and anxiety.

| Variables | Stress score | Anxiety score | Depression score |

|---|

| n | Mean±SD | p-value | n | Mean±SD | p-value | n | Mean±SD | p-value |

|---|

| Employment status of spouses |

| Employed | 84 | 24.14±3.707 | 0.869 | 84 | 19.45±6.011 | 0.505 | 84 | 16.36±5.498 | 0.896 |

| Unemployed | 16 | 24.31±4.012 | 16 | 17.94±8.512 | 16 | 16.56±6.985 |

| H/O known physical illness |

| Yes | 19 | 24.11±3.125 | 0.934 | 19 | 21±5.022 | 0.18 | 19 | 18.42±5.337 | 0.086 |

| No | 81 | 24.19±3.883 | 81 | 18.79±6.696 | 81 | 15.91±5.736 |

| Education status |

| Not educated | 12 | 24.5±3.68 | 0.9 | 12 | 17.75±8.335 | 0.709 | 12 | 15.25±7.175 | 0.752 |

| Schooling | 81 | 24.09±3.805 | 81 | 19.41±6.371 | 81 | 16.58±5.545 |

| Graduated | 7 | 24.57±3.457 | 7 | 19.43±3.552 | 7 | 16.14±5.728 |

| Type of family |

| Nuclear | 76 | 24.25±3.933 | 0.55 | 76 | 18.87±6.791 | 0.646 | 76 | 16.12±5.711 | 0.317 |

| Extended | 21 | 23.62±3.008 | 21 | 20.29±5.551 | 21 | 17.81±5.947 |

| Joint | 3 | 26±3.464 | 3 | 20.33±1.528 | 3 | 13.33±2.517 |

| Socio-economics status |

| Lower | 49 | 24.86±3.868 | 0.17 | 49 | 20.02±7.543 | 0.264 | 49 | 17.43±6.305 | 0.061 |

| Lower middle | 48 | 23.44±3.554 | 48 | 18.19±5.197 | 48 | 15.08±4.924 |

| Upper middle | 3 | 24.67±3.215 | 3 | 22.33±1.528 | 3 | 20.33±2.517 |

| Employment status of patients |

| Employed | 28 | 22.71±3.505 | 0.047 | 28 | 13.61±5.62 | <0.001 | 28 | 11.89±3.725 | <0.001 |

| Unemployed | 46 | 24.61±3.37 | 46 | 21.76±5.677 | 46 | 18.07±5.701 |

| Partially employed | 26 | 24.96±4.266 | 26 | 20.73±4.796 | 26 | 18.27±4.968 |

| Presence of male child |

| Male child present | 71 | 23.75±2.55 | 0.106 | 71 | 18.54±8.17 | 0.143 | 71 | 15.94±4.39 | 0.520 |

| No male child | 29 | 25.20±2.24 | 29 | 20.86±4.63 | 29 | 17.48±4.74 |

| Presence of female child |

| Female child present | 70 | 23.71±2.88 | 0.854 | 70 | 19±9.09 | 0.012 | 70 | 15.86±5.32 | 0.125 |

| No female child | 30 | 17.63±4.86 | 30 | 19.7±5.19 | 30 | 25.23±3.28 |

The results revealed a significant association between the employment status of patients and spousal stress, anxiety and depression scores. Spouses of employed patients exhibited significantly lower anxiety (mean difference=-8.154, p<0.001) and depression scores (mean difference=-6.172, p<0.001) than those of unemployed patients. Similarly, spouses of employed patients also had significantly lower anxiety (mean difference=-7.124, p<0.001) and depression scores (mean difference=-6.376, p<0.001) than those who were partially employed. However, no significant differences in stress scores were found among spouses of employed, unemployed and partially employed patients, although spouses of employed patients showed lower stress scores than both groups [Table/Fig-8].

Association of stress, anxiety and depression with employment status of the spouses.

| Dependent variable | (i) Employment status of the patients | (j) Employment status of the patient | Mean difference (i-j) | Sig. | 95% Confidence interval |

|---|

| Lower bound | Upper bound |

|---|

| Stress score | Employed | Unemployed | -1.894 | 0.1 | -4.03 | 0.24 |

| Partially employed | -2.247 | 0.079 | -4.67 | 0.18 |

| Unemployed | Employed | 1.894 | 0.1 | -0.24 | 4.03 |

| Partially employed | -0.353 | 1 | -2.54 | 1.83 |

| Partially employed | Employed | 2.247 | 0.079 | -0.18 | 4.67 |

| Unemployed | 0.353 | 1 | -1.83 | 2.54 |

| Anxiety score | Employed | Unemployed | -8.154* | <0.001 | -11.33 | -4.97 |

| Partially employed | -7.124* | <0.001 | -10.74 | -3.51 |

| Unemployed | Employed | 8.154* | <0.001 | 4.97 | 11.33 |

| Partially employed | 1.03 | 1 | -2.23 | 4.29 |

| Partially employed | Employed | 7.124* | <0.001 | 3.51 | 10.74 |

| Unemployed | -1.03 | 1 | -4.29 | 2.23 |

| Depression score | Employed | Unemployed | -6.172* | <0.001 | -9.11 | -3.23 |

| Partially employed | -6.376* | <0.001 | -9.71 | -3.04 |

| Unemployed | Employed | 6.172* | <0.001 | 3.23 | 9.11 |

| Partially employed | -0.204 | 1 | -3.21 | 2.8 |

| Partially employed | Employed | 6.376* | <0.001 | 3.04 | 9.71 |

| Unemployed | 0.204 | 1 | -2.8 | 3.21 |

There was a statistically significant positive correlation between anxiety scores and the age of both female (rho=0.244) and male (rho=0.363) children. Similarly, there was a statistically significant positive correlation between depression scores and the age of female (rho=0.258) and male children (rho=0.292) [Table/Fig-9].

Correlation of age of children with stress, anxiety and depression scores.

| Variables | Stress score | Anxiety score | Depression score |

|---|

| Correlation coefficient (rho) | p-value | Correlation coefficient (rho) | p-value | Correlation coefficient (rho) | p-value |

|---|

| Age | -0.085 | 0.399 | 0.131 | 0.193 | 0.096 | 0.34 |

| Child female age | -0.011 | 0.916 | 0.244* | 0.016 | 0.258* | 0.011 |

| Child male age | 0.142 | 0.239 | 0.363** | 0.002 | 0.292* | 0.014 |

Discussion

The study observed that a significant proportion of spouses of patients with alcohol use disorder had above-normal mean scores of stress, anxiety and depression. The average age of the participants was 42.1±11.7 years, in contrast to the findings of Sedain CP, where most of the spouses were aged 30-39 [6]. Also, Dandu A et al., reported a mean age of 41.24 years for participants, with a spousal age of 35.04 years, which is similar to the findings of this study [15].

The average stress score among participants was found to be 24.2±3.7, indicating a moderate level of perceived stress within the sample. In terms of anxiety, the mean score was 19.2±6.4, suggesting variability in anxiety levels among participants. Similarly, the mean depression score was 16.4±5.7, indicating varying degrees of depressive symptoms within the cohort. A study by Undkat MK et al., reported the prevalence of anxiety and depression among wives of patients with alcohol dependence to be 53.33% and 51.33%, respectively. Among these women, 9.33% experienced mild anxiety, 30.67% moderate anxiety and 13.33% severe anxiety [16]. This finding is consistent with another study conducted by Solati K and Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, which reported that wives of patients with alcohol dependence reported higher levels of anxiety and stress [17]. Similar studies from the literature have been tabulated in [Table/Fig-10] [6,15,16].

Similar studies from the literature [6,15,16].

| S. No. | Author’s name and year | Place of study | Number of subjects | Objective | Parameters assessed | Conclusion |

|---|

| 1 | Sedain CP 2011 [6] | Nepal | 46 | To assess the psychiatric morbidity in spouses of males with alcohol use disorders | Somatic symptoms, minor psychiatric illness, anxiety, sleep, and depression | Spouses of male alcoholics developed depression, followed by conversion disorder and anxiety disorder [6]. |

| 2 | Dandu A et al., 2015 [15] | Tirupati, Andra Pradesh | 101 | To determine the frequency and nature of psychiatric morbidity in spouses of patients with alcohol related disorders | Somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, sleep in spouses. Severity of alcohol in patients | The psychiatric morbidity was higher between 31- and 40 years age and among rural domicile and those who received verbal and physical violence [15]. |

| 3 | Unadkat AK et al., 2022 [16] | Gujarat | 150 | To study the prevalence of perceived stress, anxiety, depression and coping strategies in wives of patients with alcohol dependence | Perceived stress, anxiety, depression, coping strategies | Avoidance is the most popular coping skill. Screening of spouses should be done, and pharmacological or non pharmacological measures must manage their issues [16]. |

| 4 | Present study | Chennai | 100 | To assess the perceived stress levels and prevalence of depression and anxiety and their correlation among spouses of patients with alcohol dependence | Perceived stress, anxiety, and depression | High prevalence of perceived stress, depression, and anxiety among the spouses underscores the significant burden placed on family members owing to AUD. |

Family structure analysis did not indicate a significant association between stress, anxiety and depression scores and the type of family. Studies have shown that extended families are associated with a lower risk of violence against women [18,19]. In extended families, the availability of social support networks and caregiving responsibilities influence mental health outcomes. Most of the participants came from lower to lower-middle socio-economic backgrounds. Upper-middle-class individuals had the highest mean depression scores, followed by lower-class individuals and lower-middle-class individuals. However, no significant association was found between socioeconomic status and stress, anxiety and depression scores.

Significant differences were observed in stress, anxiety and depression scores based on the employment status of patients. Spouses of employed patients had lower stress, anxiety and depression scores than those of unemployed and partially employed patients and these differences were statistically significant (p=0.047, p<0.001, p<0.001, respectively). Past studies have shown that unemployment leads to heavier drinking patterns among alcoholics and increased stress due to unemployment [20]. Having an unemployed husband leads to lower median household incomes and greater emotional distress for spouses [20,21]. Furthermore, greater alcohol consumption due to unemployment may lead to increased domestic abuse and spousal violence, leading to greater levels of stress, anxiety and depression scores in spouses of alcoholics [22].

Past studies have shown that spousal unemployment leads to greater substance dependence in alcohol addicts, which can result in higher stress, anxiety and depression scores in the spouses of alcoholics. Employment among spouses leads to greater independence and may also lessen the economic burden of alcohol use on the family. However, in the present study, there was no significant association found between spousal employment and scores for stress, anxiety and depression.

The gender of children in the family also plays a role. A significant association was found between the presence of a female child and anxiety scores. A significant positive correlation was found between the age of the female child and psychological measures, including anxiety and depression scores. Similarly, the age of male children demonstrated a statistically significant strong positive correlation with anxiety scores and a moderate positive correlation with depression scores. Parents with substance use disorders are more likely to abuse their children, both physically and sexually, than non abusers [23] and this may be more evident when a girl child is present. Furthermore, the presence of a girl child may lead to anticipation that the family may need to bear more children in the future [24]. Additionally, male children of alcoholics are themselves vulnerable to alcohol abuse [23]. All these factors may increase the burden on spouses, leading to higher stress, anxiety and depression scores.

Regarding the history of physical illness, 19% of the participants had a known physical illness. However, no significant association was found between stress, anxiety and depression scores and the presence of physical illness in the present study. Past study has shown that depression scores are higher in spouses of alcoholics who have long-term disabilities or physical illnesses [25]. The presence of physical health issues can contribute to additional stress and exacerbate mental health symptoms in spouses of individuals with alcohol use disorders.

Limitation(s)

The present study consisted of spouses of alcoholics who reported to the Psychiatric Outpatient Department (OPD) for treatment. However, a large portion of alcoholics do not seek treatment and hence this sample may not be truly representative of the community. Family members of alcoholics also tend to minimise and rationalise their drinking habits, which may lead to inaccurate reporting of their symptoms. Alcohol use is strongly linked to family dynamics and multiple members of a family may indulge in substance abuse, such as the sons of alcohol users, leading to an increased burden on the spouses of alcoholics. Additionally, factors such as physical and sexual violence and economic problems arising from drinking patterns were not ascertained, which may also significantly affect the spouses of alcoholics.

Conclusion(s)

The findings revealed that most spouses in households affected by Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD) experienced varying degrees of psychological distress, including stress, anxiety and depression. This high prevalence underscores the significant burden placed on family members owing to AUD. The present study underscores the urgent need for comprehensive interventions and support systems targeting the mental health of spouses in families with AUD. Addressing the high prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression among spouses is crucial for holistic management and for improving overall well-being. Future research focusing on longitudinal assessments and tailored interventions can further enhance understanding and guide effective strategies to support spouses in AUD treatment and recovery.