Burn is an injury which is caused by application of heat or chemical substances to the external or internal surfaces of the body causing destruction of tissues [1].

However, severe burn injury is the most devastating injury; a person can sustain it and yet hope to survive. Every year more than 2 million people sustain burns in India; most of them (around 500,000 people) were treated as outdoor patients. About 2,00,000 were admitted in hospitals while 5,000 died [2].

The exact cause of death in many mortally burned patients is not known. Tests of blood, serum electrolyte values, and other laboratory determinants may be normal, yet sometimes patient succumbs to death. In such cases exact reason behind his/her death remains unsolved. Many explanations have been offered including electrolyte imbalance, shock, and infection, renal, hepatic or adrenal insufficiency. The major cause of death in the burn patients includes multiple organ failure and infection. It is suggested that they can be understood better with a pathological study of the victim’s organs [3].

In many cases, young married women die due to burns and in such cases IPC 304 (B) may become applicable. Similarly, burns may be used to cause homicidal death [1].

In modern era, commonly a big hue and cry in media (Print & Electronics) is made over such deaths and their investigations. This puts immense pressure on workers including autopsy surgeons. There are instances that post mortem reports in such cases are referred to second to multiple opinions. In some cases even a second autopsy is being performed because of this hue and cry. There are suggestions by various forensic experts, albeit defensive, to study targeted organs histopathology. However, there are studies contrary to their suggestions [4,5].

This study is undertaken in furtherance of evaluation of histopathology and acridine orange fluorescence microscopy in cases of burns of target organ kidney. Additionally, we wanted to know if there was any relationship between duration of survival and various histological changes observed in kidney due to burns.

Materials and Methods

The present study was carried out at the Department of Pathology with collaboration of the Department of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology in our hospital. An experimental longitudinal prospective study of 2 years, from October 2010 to September 2012. Total 32 cases of death due to burns were autopsied at mortuary, the Department of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology in our hospital. Clinical case records of the deceased were reviewed in all cases before autopsies were undertaken.

Inclusion criteria

All accidental, suicidal and homicidal autopsy cases of burns were included.

All the autopsy cases of burns of both genders and all age groups were included.

Exclusion criteria

Autopsy cases with history of sustaining scalds, electrocution, radiological injuries and other mechanical injuries were excluded from the study.

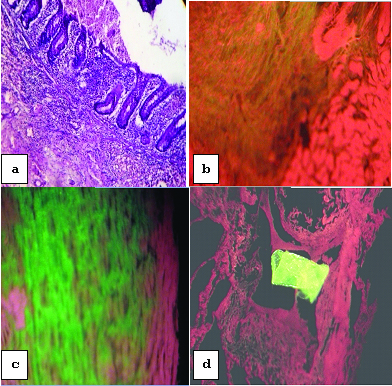

After opening the thoracic and abdominal cavities during autopsy procedure, kidneys were removed bilaterally, and preserved in 10% formalin solution. These were forwarded to Department of Pathology for histopathological examination. After proper fixation of organs in 10% formalin, grossing was done and sections from representative areas were taken and processed for microscopic histopathological examination by paraffin embedding method. Routine microscopic examination by H&E stain as well as PAS stain and fluorescence study by acridine orange stain were done in all cases. As a control of PAS stain, section from appendix was taken whereas for the control purpose of fluorescence study, a paraffin section from a case of acute myocardial infarction was taken which was showing changes of MI grossly as well as microscopically in H&E stain [Table/Fig-1].

a) PAS positive mucosal glands of appendix (Control slide- PAS stain, 40X, 54% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager; (b) lightly positive in early myocardial infarct (control slide- Acridine Orange, 400X); (c) brightly positive in old myocardial infarct (control slide- Acridine Orange, 400X); (d) Fluorescent artefact (Acridine Orange, 400X).

Acridine orange fluorescence study [

6]:

Staining procedure: 1) 1% solution of Acridine orange was prepared by dissolving 1g of the powder in 100 ml phosphate buffer of pH7.0; 2) Paraffin embedded sections were brought to water; 3) Staining with acridine orange solution is effected for 3-5 seconds, the slides being continuously adjusted during this time to avoid non-specific deposition of acridine orange; 4) The stained sectioned are repeatedly rinsed in phosphate buffer for 10-15 minutes using 2-3 changes of buffer solution. This resulted in washing away of non-specific deposits of acridine orange; 5) The sections were then mounted in buffer solution and viewed under UV fluorescent microscope immediately. At the end of the staining, the sections attained moderately dark brown colour visible to the naked eye.

Interpretation: Examination under fluorescent microscope using low power magnification revealed necrosed tissue by its grass green colour. The intensity of green colour is directly proportional to the severity of damage.

Results

In the present study, wide age range was observed from 11 to 90 years. Maximum number of cases were in the age group of 21 to 30 years (31.25%) followed by age groups of 11 to 20 years (28.12%) and 31 to 40 years (21.87%). Out of 32 cases, 28 (87.50%) were females and only 4 (12.50%) were males. So, the overall M:F ratio was 1:7. In 21 to 30 years age group, 80% were female and 20% were males. In 11 to 20 years age group, all (100%) were female while in 31 to 40 years age group, 85.71% were female and 14.29% were males. Distribution of cases according to duration of survival was 0-12 hours [Table/Fig-2].

Distribution of cases according to duration of survival was 0-12 hours.

| Duration of survival | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| 0-12 hours | 09 | 28.13 |

| 13-24 hours | 04 | 12.50 |

| 25-48 hours | 05 | 15.63 |

| 49-72 hours | 02 | 06.25 |

| 4 to 5 days | 06 | 18.75 |

| 6 to 7 days | 03 | 09.37 |

| 8 days and more | 03 | 09.37 |

All cases studies showed burns varying from 41 % to 100 %. Sparing one, rest of the cases showed more than 50% area involvement. Out of total 32 cases, 31 had dermo-epidermal burns (96.87%) and the only remaining one case had deep burns (3.13%).

In majority of cases, cause of death was septicaemia (37.50%) followed by hypovolumic shock (31.25%) and acute renal failure (21.88), while in only three cases cause of death was neurogenic shock (9.37%) [Table/Fig-3].

Distribution of cases according to cause of death.

| Cause of death | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| Neurogenic shock | 03 | 09.37 |

| Hypovolaemic shock | 10 | 31.25 |

| Acute renal failure | 07 | 21.88 |

| Septicaemia | 12 | 37.50 |

| Accidental injuries | 00 | 00.00 |

| Others | 00 | 00.00 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 |

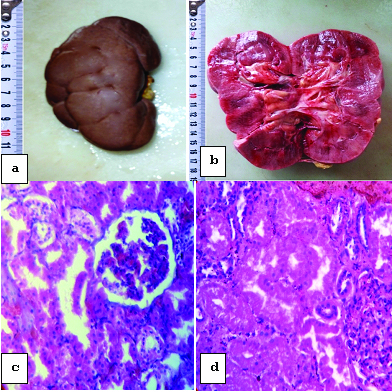

It was observed that in majority 21 (65.63%) of cases, gross findings in kidneys were normal while in 6 cases (18.75%) kidneys were grossly pale and in rest 5 cases (15.62%) heavy & congested kidneys were seen [Table/Fig-4 a,b].

a) Gross appearance of kidney showing no remarkable changes; (b) Gross appearance of enlarged kidneys showing marked congestion; (c) Microscopic changes of cloudy swelling in kidneys (H&E stain, 400X, 34% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager); (d) Microscopic changes of ATN-initiation phase showing early changes of necrosis in epithelial cells (H&E stain, 400X, 34% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager).

Sections were taken from kidneys and studied by H&E stain showed overlapping histopathological changes in all cases [Table/Fig-5]. We have distributed them according to the predominant finding observed in the particular case and correlated it with duration of survival.

Distribution of cases according to predominant histopathological changes in kidneys.

| Histopathological change | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| Cloudy swelling | 06 | 18.75 |

| Acute tubular necrosis(ATN) | 26 | 81.25 |

| Glomerular changes | 00 | 00.00 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 |

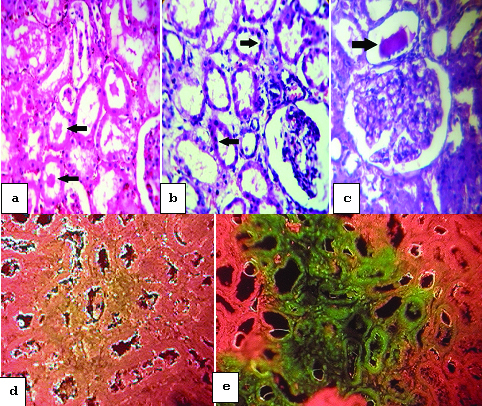

In 26 (81.25%) out of total 32 cases, changes of acute tubular necrosis were observed while in the remaining 6 cases (18.75%) changes of cloudy swelling were observed [Table/Fig-4c]. A total of 26 cases showing changes of ATN were distributed into initiation phase (38.46%), maintenance phase (50.00%) and recovery phase (11.54%) according to their specific morphological features [Table/Fig-4d,6a&b]. It was observed that 21 cases (65.63%) had predominant proximal tubular necrosis while rest 5 cases had predominant distal tubular necrosis which were further distributed into focal (9.37%) and diffuse (6.25%) tubular involvement.

a) Microscopic changes of ATN-maintenance phase showing necrotic areas and cast formation (arrows) within the renal tubules (H&E stain, 400X, 35% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager);(b)Microscopic changes of ATN-recovery phase showing regeneration of epithelial cells (arrows) (H&E stain, 400X, 34% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager);(c) PAS positive hyaline material (arrow) within renal tubules (PAS stain, 400X, 34% zoomed image in Microsoft picture manager);(d)lightly positive in kidneys (Acridine Orange, 400X); (e)brightly positive necrotic tubules in kidneys (Acridine Orange, 400X).

[Table/Fig-7] All above observed histopathological features were correlated with duration of survival and it was observed that all cases showing changes of cloudy swelling had minimum duration of survival (0-12 hours) whereas, cases showing changes of acute tubular necrosis were distributed in correlation with duration of survival into initiation (0-36 hours), maintenance (37 hours to 6-7 days) and recovery phases (8 days and more) [Table/Fig-7].

Correlation of histopathological changes in kidneys with duration of survival.

| Histopathological changes | Duration of survival | Total (No. of cases) |

|---|

| 0-12 hours | 13-24 hours | 25-48 hours | 49-72 hours | 4-5 days | 6-7 days | 8 days & more |

|---|

| Cloudy swelling | 06 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 06 |

| ATN- initiation phase | 03 | 04 | 03 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 10 |

| ATN- maintenance phase | 00 | 00 | 02 | 02 | 06 | 03 | 00 | 13 |

| ATN- recovery phase | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 03 | 03 |

| Glomerular changes | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 | 00 |

| Total (No. of cases) | 09 | 04 | 05 | 02 | 06 | 03 | 03 | 32 |

It was observed that sections taken from kidneys stained by PAS stain were positive in 23 cases (71.88%) showing PAS +ve hyaline material within tubules formed due to acute tubular necrosis and negative in 09 cases (28.12%) [Table/Fig-6c].

It was observed that sections taken from kidneys stained by acridine orange stain and observed under fluorescent microscope were lightly positive in 15 cases (46.88%) and brightly positive in 08 cases (25.00%) whereas, negative in 09 cases (28.12%) [Table/Fig-6d,e&8].

Distributions of cases according to changes observed by Acridine orange stain study in kidneys.

| Changes observed by Acridine Orange study | No. of cases | Percentage |

|---|

| Brightly positive in necrosed area | 08 | 25.00 |

| Lightly positive in necrosed area | 15 | 46.88 |

| Negative | 09 | 28.12 |

| Total | 32 | 100.00 |

Discussion

The observations of the present study and their correlation with other studies are discussed as below:

1) Age & Gender

In the present study, maximum numbers of cases were in the age group of 21 to 30 years (31.25%) followed by the age groups of 11 to 20 years (28.12%) and, 31 to 40 years (21.87%). Females (87.50%) outnumbered males (12.50%) with M:F ratio of 1:7. As young Indian females (11-40 years) are more commonly involved in cooking practice and dowry deaths are also common in this age group, the observations of present study are explanatory.

Age & Gender distribution of cases in present studies are consistent with studies of other Indian studies [7–9]. However Olaitan and colleague had different figures [10], that study was done in Nigeria, and most of the deaths were accidental. However, while in our study, as well as studies done by other Indian authors mentioned above, many cases were of dowry death [Table/Fig-9].

Comparison of age and gender.

| Study | Year | Male | Female | Age group in years (% of cases) |

|---|

| Gorea RK et al., [7] | 1990 | 29.79% | 70.21% | 21-30 (63.82%) |

| Olaitan PB and Jiburum BC [10] | 2006 | 66.70% | 33.30% | 71-80 (66.70%) |

| Buchade et al., [8] | 2011 | 37.14% | 62.86% | 21-30 (40.93%) |

| Jagannath HS et al., [9] | 2011 | 32.22% | 67.78% | 21-40 (55.78%) |

| Present study | 2012 | 12.50% | 87.50% | 21-30 (31.25%) |

2) Depth of burns

In the present study, 96.87% cases showed dermo-epidermal burns, while other studies were showing around 40%. This finding was not consistent with other studies due to variation in sample size and exclusion of cases with superficial burn [Table/Fig-10].

Comparison of depth of burns.

| Study | Year | Depth of burns | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Sharma SR., [11] | 1984 | Dermo-epidermal | 40.00% |

| Gorea RK et al., [7] | 1990 | Dermo-epidermal | 36.17% |

| Present study | 2012 | Dermo-epidermal | 96.87% |

3) Duration of survival

In the present study, it was observed that maximum number of cases (28.13%) of the victims could not survive for more than 12 hour [Table/Fig-11].

Comparison of duration of survival.

| Study | Year | Duration of survival | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Buchade et al., [8] | 2011 | 13-24 hours | 25.74% |

| Chawla et al., [2] | 2011 | 0-24 hours | 40.00% |

| Present study | 2012 | 0-12 hours | 28.13% |

Various studies that we have referred to, did not analyse these data in relation to duration of survival [7,9,11,12]. However, Chawala et al., and, Buchade et al., used their data in relation to duration of survival. The present study findings and observations are more or less comparable as shown in the table.

4) Cause of death

In majority cases of the present study, cause of death was septicaemia (37.50%) followed by hypovolaemic shock (31.25%) and acute renal failure (21.88) [Table/Fig-12]. Table showed that two studies Chawla et al., and, Tripathi CB are showing similar results, so present study is consistent with those two studies [2,12]. The present study observed septicaemia as the most common cause of death whereas, Olaitan et al., and Argamaso observed acute renal failure and asphyxia respectively as the most common cause of death followed by septicaemia [10,13]. This discrepancy may be due to different duration of post burn survival.

Comparison of causes of death.

| Study | Year | Cause of death | Percentage (%) |

|---|

| Argamaso RV [13] | 1967 | Asphyxia | 31.40% |

| Tripathi CB [12] | 2000 | Septicaemia | 30.92% |

| Olaitan PB and Jiburum BC [10] | 2006 | Acute renal failure | 42.10% |

| Chawla et al., [2] | 2011 | Septicaemia | 56.00% |

| Present study | 2012 | Septicaemia | 37.50% |

5) Gross findings in kidneys

In the present study, it was observed that in majority of cases (65.63%), gross findings in kidneys were normal while in 6 cases (18.75%) kidneys were grossly pale. In rest of the 5 cases (15.62%), heavy & congested kidneys were seen.

Most of the literature and studies mention that gross changes seen in the kidneys of a patient dying after a severe burn are not particularly characteristic. The kidneys may be somewhat congested, but otherwise appear normal [14,15]. So, the present study is in accordance with these literatures and studies.

6) Predominant histopathological changes in kidneys

We had distributed all the cases according to predominant histopathological feature observed in kidneys in each case. In 81.25% cases, changes of acute tubular necrosis were observed while in 18.75% cases changes of cloudy swelling were observed. S.Sevitt observed changes of acute tubular necrosis in 59.30% cases and changes of cloudy swelling in 37.21% cases [15]. So, the present study was consistent with above mention study.

Argamaso RV observed changes of cloudy swelling in 10.00% cases whereas, 33.33% cases had degenerative changes in the renal tubules [13]. Rest of the cases were not showing any significant changes. So, the present study was not consistent with the above mentioned study, which may be due to the difference in the post burn duration of survival.

7) Various phases of ATN

In the present study, cases showing changes of ATN were distributed into initiation phase (38.46%), maintenance phase (50.00%) and recovery phase (11.54%) according to their specific morphological features showing good correlation between duration of survival and various phases of ATN as mentioned in various literatures [16].

8) Predominant tubular involvement by ATN

In the present study, 21(65.63%) cases had predominant proximal tubular necrosis while only 05 (15.62%) cases had predominant distal tubular necrosis either focal 03 (9.37%) or diffuse 02 (6.25%), 06 (18.75%) cases had no tubular necrosis.

S.Sevitt (1956) found proximal tubular necrosis in 19.77% cases and distal tubular necrosis in 39.53% cases (18.60% with focal & 20.93% with diffuse type) while, 37.21% cases had no tubular necrosis [15]. Proximal tubular necrosis was mainly noted in adults and distal tubular necrosis was noted in children less than 15 years of age.

So, the present study is consistent with study of S.Sevitt (1956) as in the present study majority of the patients are adults having more than 20 years of age showing predominant proximal tubular necrosis [15].

9) Correlation of histopathological changes in kidneys with duration of survival

The observed histopathological features in the present study very well correlated with duration of survival and it was observed that all cases showing changes of cloudy swelling had minimum duration of survival (0-12 hours) whereas, cases showing changes of acute tubular necrosis were distributed in correlation with duration of survival into initiation (0-36 hours), maintenance (37 hours to 6-7 days) and recovery phases (8 days and more).

Argamaso observed changes of cloudy swelling in victims who died quickly of suffocation whereas cases showing degenerative changes in the renal tubules survived between 4 and 26 days; one who died 16 hours after burning also showed destructive changes. So, the present study was consistent with above mentioned study [13].

10) PAS stain in kidneys

In the present study as an experiment, histochemistry by PAS stain in sections taken from kidneys was also performed. Out of the total 32 cases, 23 cases (71.88%) were showing PAS positivity where hyaline material was formed within tubules due to acute tubular necrosis and 09 cases (28.12%) were found negative.

Cernea Daniela et al., used special stain PAS and revealed strong acidophilic, PAS (+) homogenous stores of a sphere or granular shape, either into the mesangial tissue or into the lumina of the tubules of kidney showing necrotic changes [17]. So, the present study showed good correlation with above mention study.

11) Acridine orange fluorescence study in kidneys

However it is mentioned in almost all reference books that fluorescence studies are negative in ATN [18,19], but, Chopra P and, Sabherwal U have proved that the examination of myocardium under fluorescent light after acridine orange staining is more sensitive than autofluorescence for detecting ischemia [20]. This method has previously been shown to be useful in the identification of myocardial infarcts in both humans and experimental animals. In the present study, as an experiment, fluorescence study was done in all cases. Surprisingly, it was observed that sections taken from kidneys stained by acridine orange stain and observed under fluorescent microscope were lightly positive in 15 cases (46.88%) and brightly positive in 08 cases (25.00%) whereas negative in 09 cases (28.12%).

Salinas-Madrigal L & Sotelo-Avila C (1986) observed a positive autofluorescence in the necrotic tubular epithelium of kidneys in all 12 patients with a histologic and clinical diagnosis of ATN [21]. So, the present study was not fully consistent with above mention study, may be due to low sample size.

Conclusion

Pursuing to the aims of the study, following conclusions are made:

Gross changes of kidneys may sometimes help to assess the primary cause of death in a case of burn.

Histopathological examination by routine H&E stain of vital organ like kidney would show microscopic changes like cloudy swelling and acute tubular necrosis.

Histochemistry (PAS stain) may confirm above findings, if done.

Earlier studies reported that fluorescence is negative in acute tubular necrosis, present study shows contrary result to this observation.

Microscopy by various methods like, H&E, PAS and fluorescent help in getting specific lesions in kidney due to burns. However, they do not affect or any add new tool in forensic causes of death of these cases. Therefore, in most of the cases of burns, this investigation, if done would become redundant.

The field is open for further exploration and research.